The Fine Art World's Mishandling of the Medium of Photography

In our other case study (The problem of Mass Production in Photography), we examined how the industrial enterprise of photography - ie: the camera companies and our industry "pros" - have impeded the development of this medium by abstracting the processes of photography into a limited, closed-circuit framework of proprietary technology, one that allows companies like Canon/Nikon/Sony/Adobe to more easily control the manner in which photographers develop their skills.

Here we will examine the other great navigator of this medium, the fine art world, whose institutions claim ownership not over the production and implementation of our photography equipment and processes, but over the widespread theoretical and cultural direction of the medium, as well as our societal paradigms and values about photography.

Such institutions will include fine art galleries and museums, who promote certain styles of photography over others, and collegiate fine art programs, who reinforce those values in the minds and habits of future generations of fine art photographers.

What we will find here is that, if the industrial branch of photography has impeded the development of this medium by intentionally distorting the public’s understanding of the mechanical processes of photography, then the fine art and academic communities have impeded the development of this medium by largely ignoring photography’s properties and capabilities altogether, and using their resources, their authority, and their reach to promote non-photographic skills and values over photographic skills and values.

Part 1: Photographic Structure and the Case of the Paper Collage

Let’s begin this discussion with a quick thought experiment.

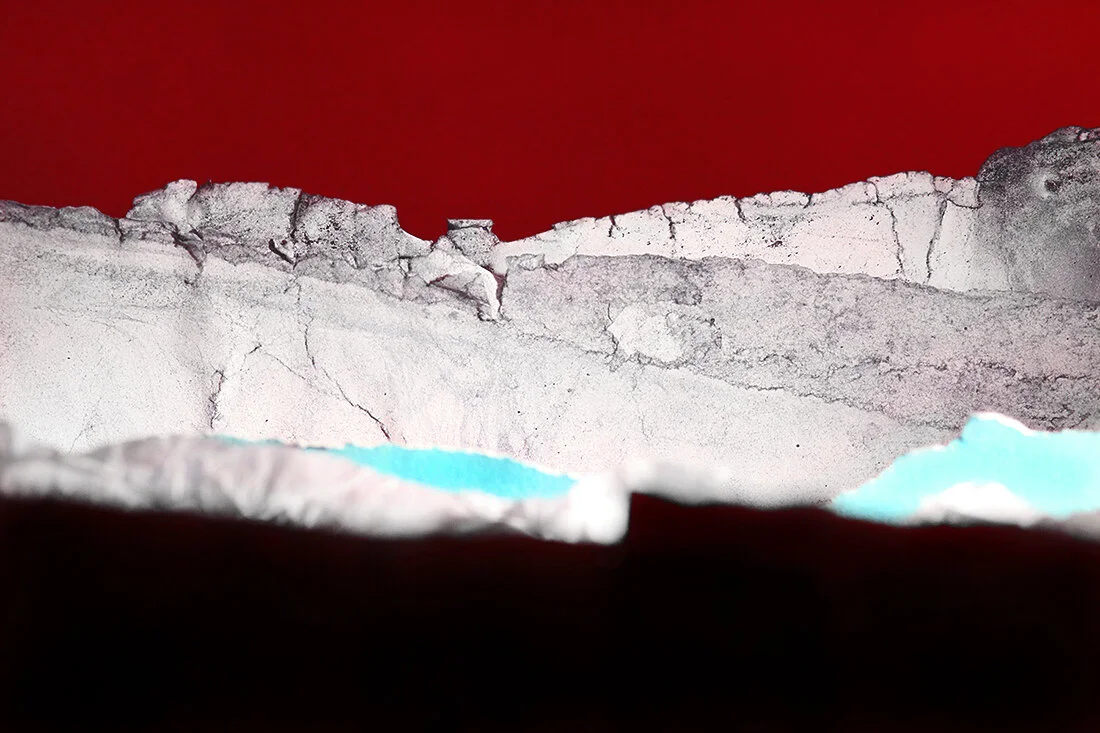

Here we have a paper collage, one that has been crafted as a physical, stand-alone art piece:

The method of creation was fairly typical for the collage process; the artist hand-dyed some strips of paper, and then fixed them together in order to form a physical, two-dimensional collage object.

But then afterward, for the purposes of cataloging, the collage was scanned by a high-resolution flatbed scanner so that it may exist in the form of a digital file, one that can be reproduced and mass-distributed, so that thousands of people may view the collage without having to view it in-person (or so that it could be included in the layout of this article, for instance).

However, consider that an alternative method for digitizing this file would be to photograph it, the way an artist often neutrally photographs a painting, or a sculpture, in order to submit a portfolio of their work to prospective galleries.

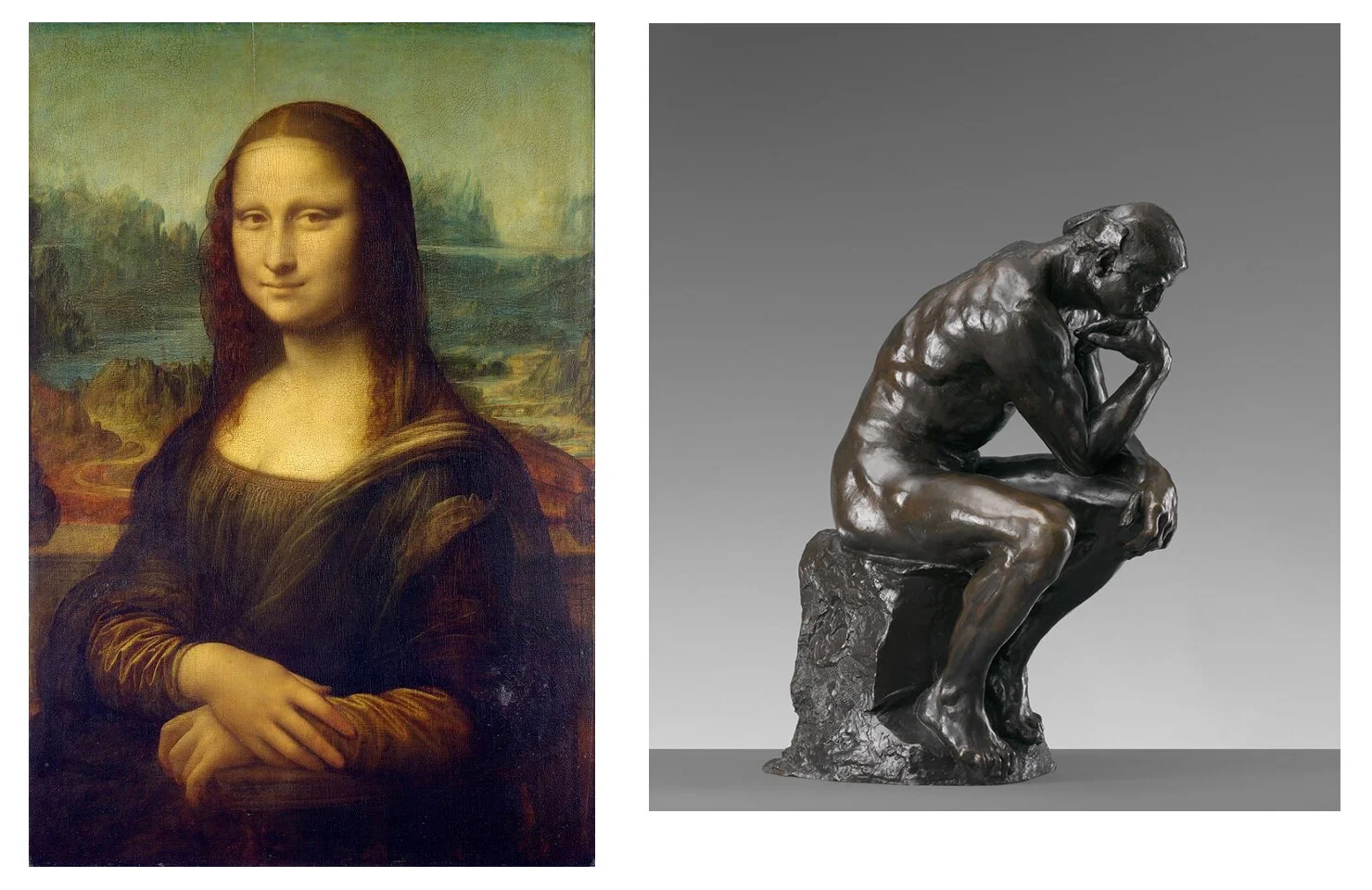

To be clear, we're not talking about photographing the collage in context, like a picture of it hanging on the wall of an art gallery, or a living space. We're talking about a photograph that reproduces the artwork as precisely as possible, cropped to the work's original dimensions. For instance, if you google the words "Mona Lisa," the images you will see in your google search are photographs of the "Mona Lisa," but cropped without any context, which causes most people to forget that they’re looking at a photograph at all; they just see a painting.

This process of neutrally recording or documenting a piece of art is called “copy work.” And when done in this manner, the photography aspect of the task is invisible and irrelevant to most people (and intentionally so), because, in most of our minds, we agree that the painting has only been photographed so that it can be reproduced online, or in a book, much like our use of the scanner here. And it is further understood that the photography aspect of the process should not add anything to the work, or alter the work in any way.

Ok, so here emerges an important question: had this collage artist used a camera to convert her collage into a digital file, instead of using a scanner:

….in other words, had she done photographic "copy work" of her collages - would the public now view her work as "photography," instead of as "collage?"

The simple answer is no. It is highly unlikely that people would view it that way.

Consider that when you go to Vincent van Gogh’s Wikipedia page and are met with “Starry Night:”

….absolutely no one gives any thought to the fact that they are looking at a photograph instead of a painting. Which is to say that it is unlikely that anyone will perceive that the real “art” they are viewing is photography, and that the painting is just sort of incidental… that the painting is merely the SUBJECT of that photograph.

Of course not.

People view it the other way around. They believe they are looking at a painting, and it’s the photography part that’s incidental.

And even if you were to prompt someone to consider the photography aspects of this specific presentation of Starry Night…..after some serious thought, the conclusion they’re likely to draw is that the method of presentation here is asking them to evaluate a painting, and not the photograph of that painting.

The photograph is merely a transparent vessel used to transmit the painting to a larger audience.

And the practical result of all of this is that people look upon this image and see “Starry Night,” and they never give the slightest thought to who might have photographed it.

Whereas the reverse is almost never true.

Almost no one looks upon this image and sees it as a work from Johnny Photographer, and asks “So what’s the subject of Johnny’s photograph here? Looks like some kind of painting, maybe?”

But embedded within that example is the assumption that the mere technicality of recording something with a camera isn't necessarily what qualifies an image to represent photography as a fine art.

We don’t consider copy work of a painting to be "Photography" with a capital “P,” because we understand that, even though photography was literally involved in some way, the considerable merits and value of the work (the true authorship of the work), don’t come from photography, rather, the merits and authorship WE ARE BEING ASKED TO CONSIDER come from the medium of painting.

We understand that the camera is only being used in order to document or transmit that merit, or to convert it into a digital copy, as had been done with the aforementioned scanner.

And underneath all of this, we understand there is a crucial difference between using a camera to record, as opposed to using a camera to express.

So finally, we now arrive upon the main crux of this essay: much of what the art world does consider to be "fine art photography" actually fails this same test.

Very often, when one visits prestigious art museums and art galleries, the work that is being presented as "fine art photography" is the result of a creative act that has been conceived, developed, and rendered entirely INDEPENDENT from photography, using entirely non-photographic skills, talents, and merits....and the camera has been introduced only to record or reproduce the concept that has been placed in front of it — ie: to record the ACTUAL art that we are meant to consider.

To illustrate, here’s a sampling of the kind of work that has become ubiquitous throughout the world of contemporary fine art photography:

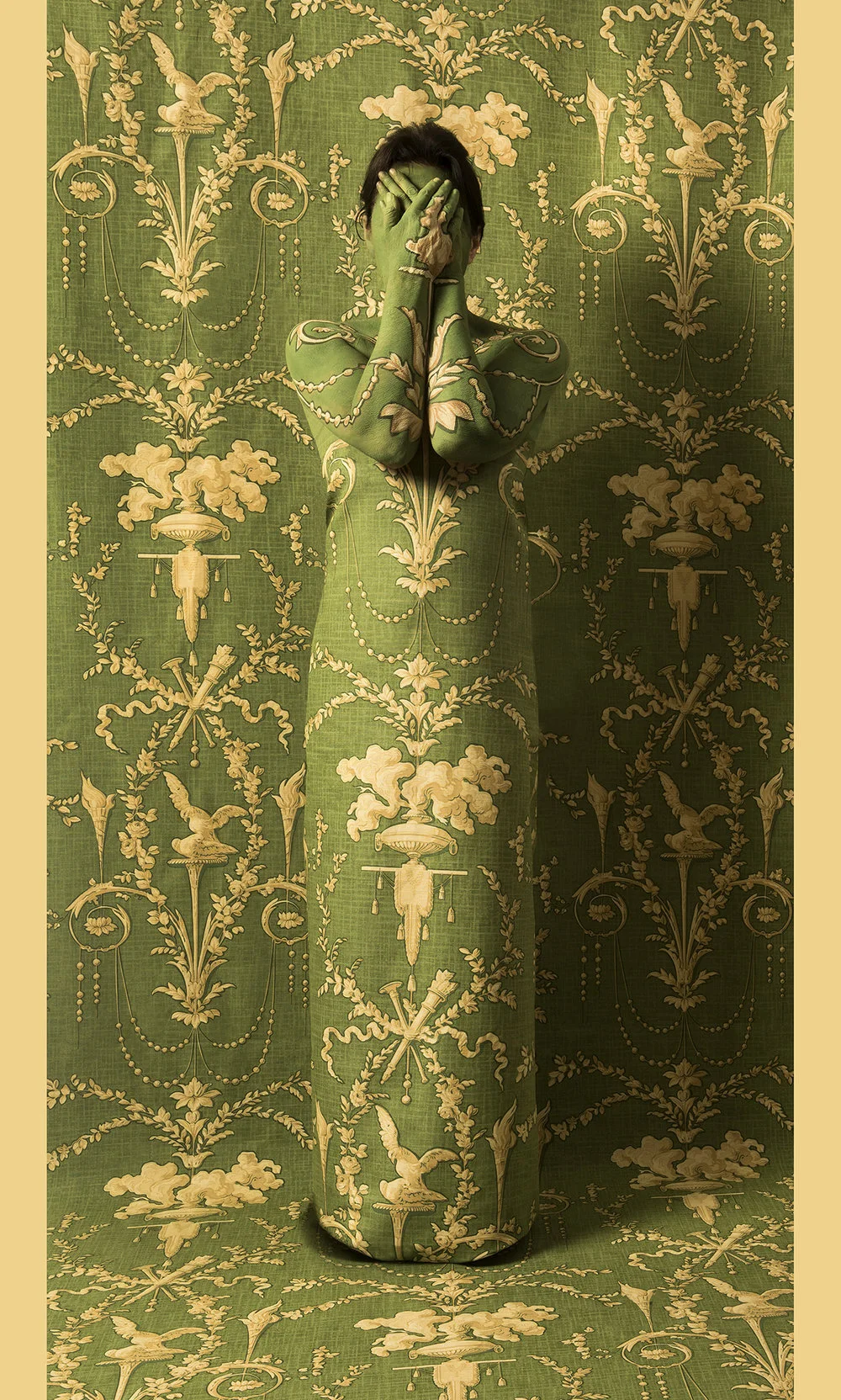

Cecilia Paredes creates matching outfits to go with her backdrops in order to generate a camouflage effect.

Haruhiko Kawaguchi shrink-wraps live human beings

Chris Buck subverts our expectations of racial power structures

Aida Muluneh pays a feminist homage to the painting traditions of her native Ethiopia

Mariel Clayton designs scenes of Barbie causing mayhem.

Eric Pickersgill removes phones from people’s hands to show the absurd ways we’ve become distant from one another.

First, these works are all very compelling to look at.

We aren’t here to dispute that.

And moreover, there’s plenty of reason to suggest that these works justify the wide-spread acclaim they’ve received.

So let’s just pause for a moment and emphasize that this is not a discussion of merit, rather, this is a discussion of taxonomy. These images are not bad art, or even “lesser” art (in fact, many readers might even prefer these works to the ones that follow), it’s that these works have been misclassified. And that misclassification poses substantial problems for the development of photography as its own, autonomous fine art medium.

For many of these pieces, the concept in front of the camera is something of a “temporary sculpture,” like a tableaux that cannot exist permanently because it uses live, human models, or a sculpture made from more perishable materials — as opposed to time-tested and more traditional materials such marble or bronze. In other cases, the concept rendered in front of the lens might be something more of a “performance piece.”

But in each case, the thing in front of the camera is the ACTUAL art, because it contains the full value of the work’s merit. And the camera has been introduced only to "scan" the performance or sculpture onto a digital file, so that it to can then be mass-distributed to people who couldn't be present to witness the performance or sculpture as it was actually occurring.

And as is the case with shooting copy work of “Starry Night,” the photographic process has been made as invisible and unintrusive as possible (the actual medium of photography has been suppressed) so that it doesn’t compete with, or interfere with, the ‘real art’ that’s on display.

In short, each of these artists has made a piece of art ….and then recorded it with a camera.

And if we return for a moment to the “Mona Lisa,” or even a picture of a Rodin sculpture that’s been printed in an art history book:

…in these instances, the “Mona Lisa,” and “The Thinker,” are both technically and literally subjects of photographs that we’re looking at.

But because ‘painting’ and ‘sculpture’ are both mediums that are so familiar and so well defined by our culture, AND ALSO because the process of photography has so purposefully been made as unintrusive as possible, the act of photographing them in such a totally neutral way can be swept aside as being incidental, as mere ‘copy work.’ We understand that the photograph is there only to deliver the value of a pre-made piece of art, and thus we are given permission to ignore the photography part altogether.

So then what IS the distinction between copy work of the “Mona Lisa,” and the fine art photography exhibited above?

Well, as far as these concepts have been established and put into practice by our culture, it would appear that for an image to be seen as ‘copy work,’ it needs to meet precisely two criteria:

1) The subject of the picture needs to be shot as neutrally as possible, so that the process of photography is not in any way noticeable, and does not “interrupt” our appreciation of the subject itself.

2) The subject of the picture needs to be a well-established and well-known creative act, one that’s already been clearly labeled and defined by our culture.

And the ‘fine art photographs’ above certainly meet the first criterion, insofar as they’ve been shot very neutrally (a point which will be much more thoroughly illustrated later in this discussion), but the confusion comes from the fact that they have little chance of meeting the second criterion, as we have no well-defined familiarity with the notion of a "perishable sculpture," or “split-second performance piece,” as an art form.

And while such creative acts undoubtedly offer tons of artistic merits and insights in their own right - as their own fine art mediums - because we have no such paradigms, we've lumped those efforts in with photography itself, to the extent that such completely non-photographic endeavors now piggyback atop the medium of photography, and are now just perceived as “photography.”

And as a side note, performance art in particular seems to have had a hard time finding a suitable home. It’s a medium with a wide-open frontier of possibilities, and it exists probably in its purest form (read: least compromised) when performed live, in front of a small, intimate group of people. But if it is to find a larger audience it often needs to piggyback atop another medium, either photography as we're discussing here, or very often avant-garde cinema or theatre (like the abstract, "one-man show" type performances common to small theater spaces). The unfortunate choice a lot of performance artists have to face is that they can either remain true to their purest visions, working in relative obscurity, and playing to very small audiences one at time, or if they want to build a larger reputation for themselves they have to merge with other, more established, and more easily distributed media, such as photography, theatre, or film.

But it isn't just sculptors and performance artists that do this; fine art photography galleries are also filled with a lot of “found objects,” or "cultural observations." This is a genre of photography in which artists find something in the world that they think is inherently meaningful or interesting, and then proceed to "show" us this found object.

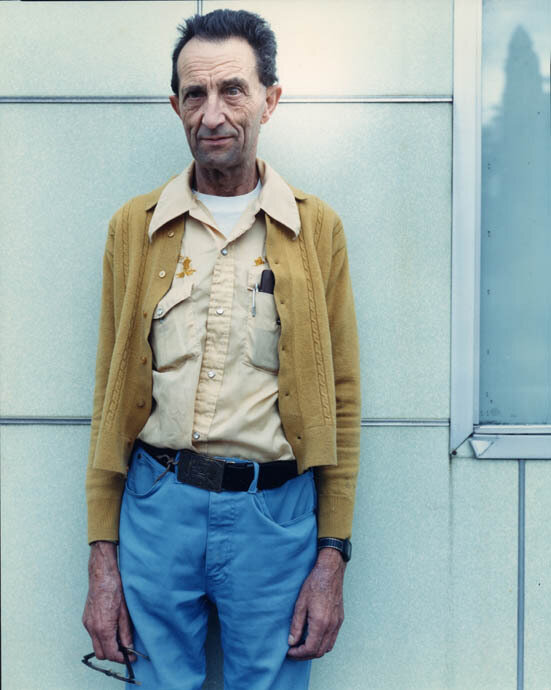

Here are some examples drawn from the popular genre known as “dead pan” photography (which is a branch of ‘postmodern photography’). Essentially, these images are copy work, but instead of neutrally recording a performance piece, they neutrally record a “found art” object:

Stephen Shore

Erik Pawassar

William Eggleston

Bryan Schuutmat

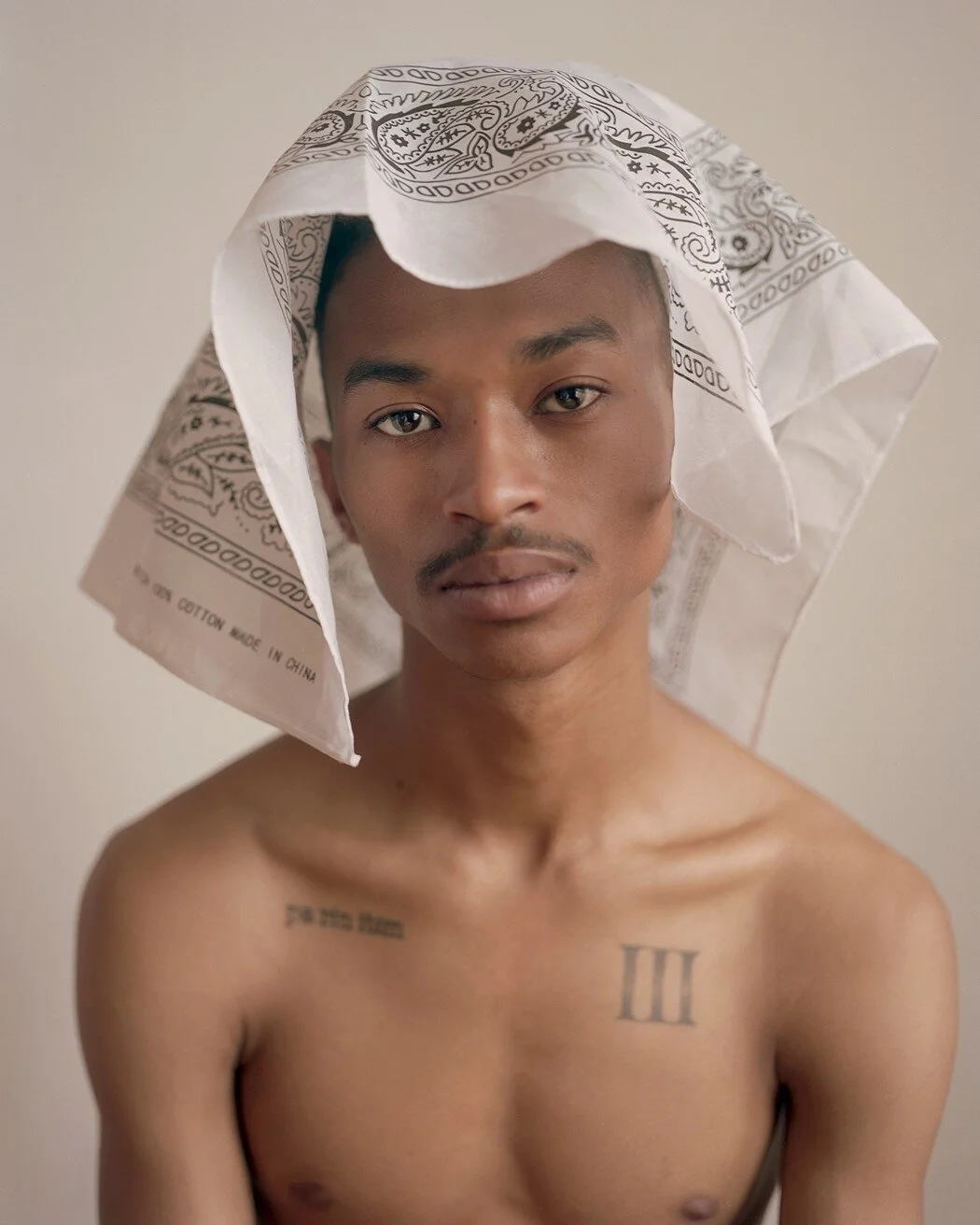

And then yet another prevalent category of fine art photography, and one that is almost a hybrid of these first two genres, is what we refer to around the ASOP studio as the “profoundly-staring-into-the-human-soul” genre, in which photographers take a fairly straight-forward snapshot of a lone human being who has been instructed to stare very seriously and very soulfully into the lens:

John Edmonds

Ella Perez

Bruce Wrighton

Bettina Von Zwehl

The works in this last genre are still rooted in “performance,” or “human sculpting,” it’s just the concept has been stripped down to its most minimal essence, giving it the simpler dead-pan feel of the “found object” category above.

But this category, in particular, has been one of the most ubiquitous and most celebrated staples of the gallery scene for decades, and it continues to be ubiquitous today. In fact, several of these shots here were pulled from the most recent Whitney Biennial show, which, for those who don’t know, is arguably the most prestigious stage on which the powers-that-be showcase up-and-coming photographers, leading many of them to become the next darlings of the art world.

And yet, once again, the considerable merits and insights of these works have little to do with the way the medium of photography has been used, or the particular manner in which photography can offer unique expressions and configurations that other media cannot.

And once again, the medium of photography itself has been neutralized, in fact, made to be as invisible and subjugated as possible, in order that it not interfere with the found objects these artists wanted to show us.

So each of these first three genres uses photography merely to record, and then mass distribute, a performance, a sculpture, or a found object. And in each case, the subject of the photograph contains the full value of the work’s merit, while exactly none of the work’s value can be attributed to photographic authorship.

Thus there is no theoretical, or logical, distinction between these works and the “copy work’ that is routinely done for other artistic mediums.

However, the distinction in practice is that, for these images, the public truly seems to believe that these instances of using a camera to neutrally record a non-photographic talent are indeed works of “fine art photography."

So why the inconsistency?

Well, herein lies the problem:

Photography has a long history of having served at least two purposes in our culture:

1) First, it can be used to document or record things of value that already exist (ie: to "scan" things), so that those things can then be reproduced and mass distributed, or kept for an official record - like photographing Rodin's sculptures so they can be displayed on his Wikipedia page, or taking pictures of your fender-bender to send to your auto insurance company.

2) Photography is also recognized as an artistic medium in its own right, because it possesses properties and EXPRESSIONS that set it apart from other media.

But because photography is recognized as being both of these things, there is often an identity conflict, a confusion of purpose, and the way it has played out until now is this:

If the SUBJECT of a photograph can be classified as an already established and familiar art form (like a painting, a marble sculpture, or a collage) then photographing it very neutrally isn't considered PHOTOGRAPHY, it is merely considered “making a record” of another art form…..it’s considered ‘copy work’..….. However, any OTHER artistic act that can be neutrally photographed is considered "PHOTOGRAPHY.”

And this an entirely superficial distinction. This isn’t something that has been brought about consciously or intentionally, through logical consideration; this is more the product of inertia, it’s a lazy distinction that’s been assigned mostly by default, and by a culture that hasn’t entirely thought through the various intricacies and consequences of photography as an art medium, nor how to identify and classify them.

But unintentional or not, this framework has been responsible, time and again, for undermining photography’s greater development.

Part 2: The Ongoing Subjugation of the Medium of Photography

So before we demonstrate some of the ways that photography can be used as an expressive medium in its own right, and not merely to record other kinds of creative talents, let’s first discuss the harm this current paradigm has done to photography’s development, as well as to its existential autonomy.

For starters, this paradigm has allowed fine art photography to be colonized by other mediums.

How so?

Well, what has been typical since at least the mid part of the 20th Century is that other kinds of less established artistic talents, unable to find a home anywhere else, often exploit the fact that photography IS a well-established medium, with a solid gallery infrastructure and plentiful MFA programs…. but it is also a poorly defined and misunderstood medium.

And thus, a lot of under-appreciated talents have found it easy to commandeer the direction of fine art photography — or to impersonate photography by way of the medium’s most literal definition — in order that they may advance the development and value of their own creative skills, as opposed to photographic skills.

In other words:

Whereas painters, bronze sculptors, and collage artists enjoy their own established positions within the art world, and have thus been content to use photography only to record and distribute their already-recognized and legitimized art forms…. having found that avenue closed to them, “performance artists,” “perishable sculptors,” and “found art seekers” have used the loopholes in the selective and inconsistent definitions we apply to photography in order to find a larger audience for their own talents…by way of using photography’s infrastructure and reputation as their own.

Or to put it as simply as possible, they’ve found it easier to label themselves “photographers” than to use what little infrastructure and reputation had been established for their own unique mediums of “performance art” or “perishable sculptures.”

But let’s get back to the notion that photography is a misunderstood medium and explore that a bit more thoroughly, because that aspect is key to unraveling how we arrived at photography’s current position in the art world.

Part of the blame for our culture’s misunderstanding of photography can be attributed to the medium’s ongoing comparison with painting, particularly with respect to the ways our public values photography, and also how our public views the role of photography.

Painting and photography are often taught hand in hand as sister visual media, and moreover, photography often serves as a precursor to the medium of painting in practice (for instance, when a painter makes a photographic study of a subject before painting it).

This leads to a lot of assertions, often implicit, that painting is a natural analogue for photography.

But when examined more closely, painting turns out to be a surprisingly poor analogue for photography, as the two have little in common aside from the fact that they are both two-dimensional, visual media. When we examine the specific skills, or the parts of the brain, that need to be developed in order to excel at each of these tasks, and more to the point, when we examine the cultural uses that are being facilitated by each medium, the comparison between photography and painting falls apart pretty quickly, as it turns out they have very little in common at all.

In many important respects, and in ways that are more pertinent to this discussion, the better analogue for photography is writing. Clearly not from an aesthetic standpoint (the two obviously look nothing alike), but practically speaking, if one considers the role that each medium plays within our society, and, more academically speaking, if one considers the ‘referential’ relationship that each medium holds toward its own subject matter, then we will find that photography analogizes far better with writing than it does with painting.

First of all, the medium of writing serves similar cultural purposes as does photography in that writing can act as both a recording device - to record legal testimony, or the minutes of a corporate meeting - and can also be used as an expressive, artistic medium in its own right, when it's in the hands of William Faulkner or Gertrude Stein.

And when it comes to writing, our culture seems to understand this distinction immediately and unambiguously. For instance, when a court stenographer types up a poignant and impassioned speech that has been delivered by an esteemed judge, no one gives any real credit to the stenographer, as it is very clear to us that the typed transcript is merely a ‘record’ of the speech.

Conversely, when we read a poem, such as “The Angler’s Song,” by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, we understand the writing to be the art. We appreciate that the topic of a “fishing trip” has been used merely as a vessel through which the author can deploy his writing skills, and in doing so, transmit deeper insights about the human condition.

Thus, to declare that reading a typed inventory or manifest from an actual real-life, commercial fishing expedition is essentially the same experience as reading “The Angler’s Song” would be universally recognized as silly. Despite the fact that both examples would share the same literal topic or subject matter (a fishing trip).

Because with writing, we know that it isn’t just the literal, recorded content alone that matters, it is how the actual medium itself has been uniquely used to address or describe that content. And we would say that Longfellow’s work is an example of writing as a creative medium, or writing with a capital “W,” whereas a typed inventory from a real-life fishing expedition is an example of writing with a lower case “w.”

Or perhaps a more poignant analogy, and one that might better demonstrate how easily we can compartmentalize these issues with writing, is to imagine a government clerk passing someone a written note that reads “Congratulations, you’ve just won the State Powerball Lottery,” and the recipient of that note immediately declaring said clerk to be a better writer than James Joyce, simply because they preferred the content of that note to the content of “Ulysses.”

A similar analogy can be made from a trial defendant reading a verdict slip from the jury that says “not guilty,” or a hospital patient thinking the technician who wrote “negative” on his lab tests to be the greatest writer of all time!!

Again, silly.

Because with writing, we rarely confuse the merits and talents of the writer with our own impulsive preference for the topic, or the literal content, of the writing.

But with photography, we make that mistake all the time. We frequently celebrate the image whose subject matter we like best, as opposed to celebrating the image that better demonstrates the articulate skills of the photographer.

Most commonly these standards can be seen in local, hobbyist photo contests, which are invariably judged by the popularity of subject matter alone, and where the winner is often the photograph with the cutest kitten or infant, or the prettiest sunset or flower. Very rarely are such contests judged according to the poetic articulations of the photographer, or the command the photographer has demonstrated over the medium.

But the entire purpose of this essay is to clarify that those standards aren’t at all confined to the local, hobbyist photo contest. Legitimate fine art critics and curators are doing very much the same thing at the broader, societal level.

That is, they judge and curate photographs based exclusively on the content that they personally deem to be most socially poignant, and not at all based on how that content was addressed, articulated, or expressed by the author’s photographic choices and skills, or how well the photographer has uniquely mastered this medium.

To put it bluntly, if those critics and curators were to evaluate the written novel by the same standards they use to evaluate photography, many would dismiss “Moby Dick” outright, for the simple reason that they don’t personally relate to, nor personally care for, the topic of “whaling,” nor do they find the topic of “whaling” to be particularly socially relevant at the moment. They wouldn’t give the slightest thought to how Melville had structured his novel, or how he’d deployed his uniquely-mastered writing skills, or how, at the broader level, he’d advanced the medium of writing so that those who follow in his footsteps might be able to push their own novels even further.

No, they would merely critique the literal subject that had been chosen, and if the topic of whaling wasn’t of any specific interest to them, they’d reward the writings of someone else, someone who had chosen a topic that they did find compelling (no matter how crude or inept their actual writing skills may be).

Which means in essence, contemporary photography critics and curators subscribe to the very same paradigm as the local photo-club contest, they’ve just replaced kittens and sunsets with their own preferred content, ie: more “culturally-charged” subject matter aimed at disrupting societal norms and values (disaffected youth, cultural taboos, identity politics, etc.).

No thought at all has been given to whether the photographer has deployed any masterful fluency in the medium, or whether they’ve moved the needle on advancing the uses and complexities of photographic syntax.

But one of the reasons we can see the duality of writing so distinctly and unmistakably is that we have well-established, and well-practiced cultural paradigms for doing so. We’ve become so culturally acclimated to seeing each of these roles that we’re now very adept at distinguishing them upon sight. Thus, when writing is used strictly to RECORD something, we almost never confuse it for being fine art.

However, our culture is not as adept at recognizing photography’s very similar duality, as our fine art galleries and museums are filled to the brim with images in which a camera has been used merely to record something.

And moreover, we aren’t even particularly logical or consistent about our values even within that practice, because whenever a photograph is used strictly to record something within the art world, we then have two very arbitrary and conflicting standards about it:

1) If the photograph neutrally records a WELL-KNOWN ART FORM, then we consider it to be “copy work.”

2) If the photograph neutrally records an UNFAMILIAR ART FORM, then we consider it to be "Fine Art Photography."

To put it as simply as possible: fine art galleries would never hang copy work of the ‘Mona Lisa’ in place of the actual ‘Mona Lisa.’ But they will hang copy work of a performance piece in place of hosting the actual performance.

One of the more significant problems with analogizing photography to painting is that many in our culture believe every instance of ‘painting a picture’ to be art, or to be expression, and that ‘painting a picture’ can never act as a mere ‘recording’ device.

Which is why, in terms of purpose (not aesthetics), writing is the better analogue here, because analogizing photography to painting often obscures the multitude of cultural purposes that photography can serve. And one of the more notable results of all of this is that we currently have one segment of our society (the art world) absolutely convinced that using a camera as a neutral recording device can qualify as artistic expression, while another segment of our society (the insurance industry) spends untold hours examining the recorded photographs of traffic collisions in the pursuit of settling insurance claims.

And we can be absolutely certain that the last thing that would ever occur to an insurance claims adjuster is that the endless stream of cell phone fender-bender pictures they sift through on a daily basis should ever be classified as ‘artistic expression.’

Or the same can be said of any typical citizen who snaps a cell phone shot of their parking space number at the airport before they hop on a plane and head out of town for a few weeks.

These uses of photography are unambiguously considered to be record-keeping, and not artistic expression.

But perhaps the greatest harm being imposed by our culture’s loose and inconsistent standards about photography is that, under the current paradigm, photography is acting as something of a generic “catch-all,” collecting all the leftover acts of creativity that haven’t already been claimed by other mediums.

In other words, as long as contemporary fine art photography is understood to be "any creative act recorded with a camera….so long as that creative act HASN’T been claimed by another medium," it means that photography is being NEGATIVELY defined. It’s being defined for what it isn’t, as opposed to being defined positively for what it is, for its own unique capabilities.

It also means that photography is being defined by, and at the mercy of, other art forms, which sharply undermines its autonomy as a medium (painters, for instance, don’t especially have to worry about not being sculptors, they enjoy the pleasure of being defined for what they are, not for what they aren’t).

And all of this pushes photography into something that exists in the negative space BETWEEN other art forms, essentially converting photography’s role into being a “default” state, or a starting point — sort of an “art-world Limbo” — for any unestablished medium, until that medium eventually earns its own label.

Or to put it another way, if the only thing preventing an image like this one from being called copy work…

….is the fact that the medium of “human sculpting” hasn’t been officially recognized or validated just yet, then it means photography is being relegated to a more remedial stage of art, existing as “pre” period for any medium that has higher aspirations to evolve into an art form recognized entirely for its own merits.

And this reduces photography to a mere ladder for other art forms to climb, or a publicity mechanism that other mediums use simply to gain more exposure.

And all of this amounts to a rather tragic, and, frankly, very insulting disenfranchisement of a highly dynamic and immensely potent medium.

Because there is a uniquely useful and insightful set of capabilities being ignored in all of this.

When photography is used for its own expressive capabilities, and not merely to record other types of skills, it has the potential to be the most effective medium in modern culture. It can bend and manipulate our perceptions about the world in ways that other media can’t, giving it a unique ability to influence our societal thinking, as well a unique potential to unlock key insights about human perception.

And perhaps most significant of all, photography’s grander ability to generate a VISUAL LANGUAGE out of the very world around us suggests that this medium has semiotic powers that need to be explored more thoroughly for their own merits, and not just how they can be used to record and promote other kinds of artistic talents.

In fact, on that last point, there is little if nothing left to explore regarding how a photograph can neutrally record something. We’ve more or less arrived at a stage where photo artists are simply recording different things, all while using the exact same neutral, ‘copy work’ process to do it. Which is to say, in most fine art photographs, the PHOTOGRAPHIC authorship is virtually identical (the image is always structured the same way), the artists are just filling in the blank with different subject matter.

It’s a bit like writing the same templated sentence over and over and over again, and just swapping out the noun.

But it really needs to be reiterated here that photography has its own uniquely variable kind of visual grammar. Specifically: the grammar and the syntax of “situation.” Which allows for this medium to express the exact same scene or situation in hundreds of different ways.

And the ability to spin any given circumstance one encounters into an expressive, linguistic articulation is a profound game-changer in terms of human language and thinking.

Consider all of the insights that could be cultivated if people were given a very keen and conscious understanding of the many ways that the exact same situation can be “read,” or understood, or presented, or perceived.

But right now all of that linguistic capability — and all of that potential expansion of human consciousness — is being wasted and ignored in favor of “pointing” at neat and exciting objects.

And this is happening across all of our most well-funded art institutions…. as well as in all of our most prestigious MFA programs.

Part 3: When the Merits of a Photograph Stem from the Actual Medium Itself.

In our next section we’ll compare the preceding works with some works from artists who are using their cameras to express, rather than to record.

But in order to understand more precisely what those photographers are doing, let’s first go back to that paper collage at the top of this article, and let’s conduct an experiment that will hopefully assist in distinguishing the properties of the medium from the subject that it’s addressing - properties that also distinguish photography from other forms of art.

Doing so will also clarify what it is we mean when we discuss “photographic authorship,” or “photographic structure and syntax.”

Because the obstacle we have to overcome here is the fact that most people are so distracted by the subject of a photograph, they don’t really notice the underlying medium that’s being used to present, or express, that subject.

So in the interest of unveiling this medium, let’s do a quick experiment.

If the photographers we looked at above did their very best to hide the medium so that their photographic decisions wouldn’t at all distract from their subject matter, let’s now do the exact opposite. Let’s purposely avoid any compelling subject matter so that it doesn’t distract from our ability to see the actual medium itself.

First, let’s take one more look at that original collage:

If this piece was created using traditional collage methods (ie: by assembling strips of paper into a physical collage), then for comparison, let’s try something different. Let’s start with the same subject matter (some strips of paper), but instead of assembling them as a collage artist would do, let’s address them, and mold them, the way a photographer would.

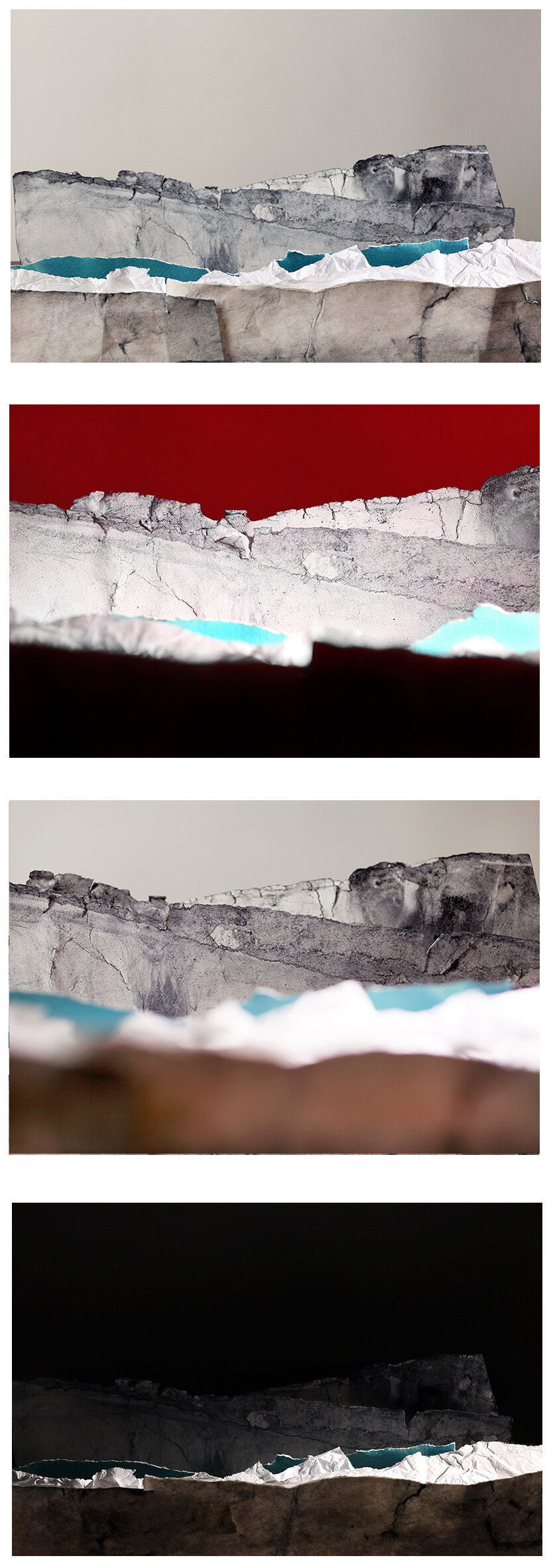

For starters, we’ll lay them out on a table, upright, and spaced apart like so:

The reason we’re going to do this is because one of the key, inherent properties of the medium of photography is having to use your lens to negotiate different layers of space. And if the strips of paper all exist on one single plane of space (as would be the case if we were photographing an actual collage), then we would have no photographic choices to make with our lenses.

However, if each strip of paper occupies a different layer of space, it means we can make discriminating choices with our lens. Specifically it means we can choose which layer of space (or which strip of paper) to emphasize within our shot.

It should be noted here that the ‘copy work’ protocol openly attempts to neutralize this aspect of photography by making sure the entire scene is as flat as possible (or as equidistant to the lens as possible). The reason being that when the scene is arranged in that particular way, then if you bring one part of the scene into focus, you’ve brought the entire scene into focus.

In other words, they want there to be no spatial disparity whatsoever, so that the photographer does not have to make any discriminating choices with their lens. They want to create a scenario wherein “one focus fits all.”

But in our case, because we have spaced our content apart, we CAN make discriminating choices. For instance, we can use our lens to mix and match different kinds of focus, depth of field, distortion, and scale dimensions, each of which configures the resulting image in a way that is unique to photography’s capabilities, and could not be rendered by the medium of collage alone.

So let’s do it. Instead of neutralizing that property of the medium, let’s actually use that property.

First, if we wanted to, we COULD render an image that looks very similar to an actual collage:

Shot 1A

Believe it or not, that’s the exact same set-up that was shown in the overview shot above:

….we’ve just used a very compressive lens in order to make the strips of paper seem closer together than they are, which gives the image a very two-dimensional look, much like an actual collage (you might say this photograph is trying to “mimic” the look of a collage, without being produced as one).

And so far that’s just one single photographic choice we get to make - how compressed we want to paper to appear.

But the strips of paper are, in reality, still spaced out upon the table. Which we will now prove in our next image.

So here we’ll use the properties of focus and depth of field in order to emphasize one layer of space as opposed to another:

Shot 1B

Ok, so that’s yet another photographic choice we get to make - how sharp (or soft) we want each respective layer of space to appear.

Next, spatial differentials are what we at ASOP call "enabling" differentials, meaning that, now that the paper strips are spaced apart, it paves the way for other photographic variables to be exploited as well.

For instance, another important photographic property (or skill) is having to negotiate different amounts of light that exist in front of the lens.

If we have different amounts of light in front of us, it means we can make discriminating choices with our camera’s exposure, which, in turn, can alter the emphasis of the image, or the complexion of the image, or the mood of the image.

And yet again, the ‘copy work’ process very intentionally nullifies this dynamic by equalizing all of the lighting within the shot. Because if all parts of the scene are lit equally, then all parts of the scene will also expose equally, once again making it impossible for the photographer to make any discriminating choices with their camera.

In other words, they want a scenario in which “one exposure fits all.”

And to repeat, the reason copy work photographers neutralize all of these dynamics is to ensure that no decisions can be made that would allow the process of photography even to be noticed, so that the photographer’s decisions don’t overshadow the subject itself (in other words, people want to see the Mona Lisa, not what the photographer did to the Mona Lisa).

So once again, instead of neutralizing and SUPPRESSING our medium, let’s liberate the medium of photography, and actually allow it to play a role in our creativity and our expression.

Being that the strips of paper are now separated from each other, they can now be lit differently from one another as well (which was near-impossible when they were pressed together as a flat collage).

That means we can light each layer of paper from different angles.

For instance, some can be lit from the front, while others can be lit from behind. We can also light each strip of paper with a totally different AMOUNT of light, which allows us to use our camera’s exposure mechanisms to emphasize one layer of paper over another, as has been done here:

Shot 1C

Again, that’s the same set-up as before - the same strips of paper - we’ve just lit and exposed them differently.

So now we have yet another set of photographic choices to make.

For instance, we can set our exposure for the brighter layers of paper, or we could set our exposure for the darker layers of paper.

In other words, we can shift our exposure settings in the same way that we can use our lens to shift focus, depth of field, and spatial compression, which means that so far, with just these two variables, there are already hundreds of realistic combinations for how we can render and configure our final "collage."

But let’s keep going.

We can also use colored gels (which basically just means “colored lights”) to light one layer of space as a different color than the others. Here we’ve lit the farthest layer of paper with a red gel, while the nearest layer of paper hasn’t been lit at all:

Shot 1D

So now we’ve lit each layer of paper even more differently from one another, which provides even more creative choices that can be made with our camera.

But hopefully it’s becoming apparent by now that this experiment is just one big exercise in control and variation, wherein we’ve “controlled” the subject (it’s the exact same strips of paper in every shot; they haven’t been moved or rearranged in any way), yet we’ve also been able to impose hundreds of potential photographic constructs onto that subject.

Which is true for ANY subject, by the way, including each and every one of those more “compelling” subjects we viewed at the top of the essay.

So revisiting those first shots for just a moment, consider that those images have all been structured in exactly the same way. Those were 14 very acclaimed and very successful photographers, and yet all of them shot their subjects IDENTICALLY.

But to conclude this discussion on the origins and purposes of the ‘copy work’ construct, the main idea we’re trying to establish here is that the ‘copy work’ protocol actively tries to eliminate, or neutralize, every single one of these photographic properties, so as to remove any possible variation in the way the subject can be recorded.

The whole point of that construct is that it’s a permanently “controlled” formula, and it never “varies” in any way.

Thus, whenever photographers are commissioned to do it, they always make sure the lighting is as even as possible, they make sure the entire scene is equidistant to the lens, and they make sure nothing in the shot is moving or changing — absolutely no photographic variables, no noticeable photographic properties, no technical decisions that have to be made — all so that the photographer CAN’T make any structural choices. Which in turn, allows the painting or collage to more neutrally speak for itself.

Or in short, the ‘Copy Work’ protocol has been intentionally designed so that the photographer can have no voice in how the subject is toned or expressed, or how the subject might be perceived or digested by the viewer.

Which makes total sense when one is rendering copy work of the ‘Mona Lisa.’

But it makes far less sense when examining an image that has been presented to the public as “an accomplished and groundbreaking work from a studied PHOTOGRAPHIC artist.”

So at the end of the day, the basic gist of this experiment is that two different types of artists - a collage artist, and a photographer - each began with the same content (some strips of paper), and each has utilized their own medium’s properties in order to address that content, or to sculpt something out of that content.

And this here is copy work of a COLLAGE:

And these here are works of PHOTOGRAPHY:

Each of these respective works is an expression of the unique properties and capabilities of these two very different mediums.

That includes by the way the very first image in that “photography” stack - the one that looks very much like a paper collage.

Because while that shot mimics the form of a collage, or “borrows its syntax” from the medium of collage, it was undeniably created using photographic methodology…not collage methodology.

And that’s the distinction we’re trying to establish here. That there’s a significant difference between using collage skills to create a notable piece of art, and then learning just enough about a camera to be able to “record” it…….as opposed to using actual photographic skills in order to generate 1) the merit, 2) the insight, and 3) the aesthetic value of the work.

It’s a profound distinction.

And to our observations it’s a distinction that the fine art photography community honestly doesn’t seem to understand.

So just to be as clear about this as we can, here’s the entire thesis of this essay in one concise summary:

The majority of contemporary fine art photographers are using a shooting protocol that has been designed for “copy work,” which is a shooting protocol that has been consciously engineered in order to nullify the expressive value of the medium of photography. In fact, it’s a process that’s been meticulously engineered to guard against any expression at all on the part of the photographer.

And then after using that formulaic protocol again and again, their work is being presented to the public — and to future generations of photographers — as “the vanguard of fine art photography,” or as the very pinnacle of what this medium can do….simply because they’ve applied that identical method to a slightly different subject matter each time.

And this is a massive, massive problem for anyone at all concerned about the development of photography as its own artistic medium, and as a sophisticated visual language in its own right.

And while this collage experiment may have seemed a relatively abstract and round-about way to demonstrate all of this, again, the reason we’ve chosen this demonstration is because, in removing any distracting subject matter from the work (i.e.: there are no naked bodies, no politically charged symbols), we are left only with the medium itself, which makes the medium a lot easier to see and comprehend.

Or, as stated before, if the photographers above tried to make the medium as invisible as possible so as not to distract from their subject matter, here we’ve done the opposite, we’ve eliminated any compelling subject matter so that it doesn’t distract from the ability to see the medium.

However, now that all of that has been thoroughly established — and in order to begin swinging the pendulum back in the other direction — let’s finally acknowledge here that yes…of course this medium is at its very best when it’s also being applied to compelling subject matter.

In other words, we want both: we want complex, skillful articulations….AND we want intriguing content. Because when complex photographic expressions are applied to compelling content, that’s when we uncover some truly profound and groundbreaking insights. It’s also when artists can begin generating more uniquely complex and individualistic expressions about the world.

So to be totally clear, the intention of this essay is not to advocate for ridding photography of all intriguing content.

Far from it.

The intention here is to call out the very large population of artists who call themselves ‘photographers,’ who aren’t using (or even learning) this medium in any substantive way at all, and who, in doing so, aren’t advancing the greater capabilities of photography, or expanding the “language of photography”….artists whose work, if anything, veers us further from developing this medium.

And perhaps more to the point, the intention here is to call out the photography community at large for continuously rewarding and promoting such works, as opposed to works in which photography itself has been explored or expanded, or works in which photography itself has played at least SOME role in our discovery of, or our perceptions of, the insights the photographer wants us to have about their subject.

Because for much of the fine art photography filling galleries today, if we are to discover or conclude anything profound at all, that conclusion usually comes directly from the subject that was chosen, and not from the way the medium of photography has been used to transform, filter, or extract anything from that subject.

And all of this leads us implicitly to a very important question: Why is photography the only medium treated with such kid gloves?

Other art forms are routinely subjected to standards and expectations that spark structural criticisms. And then those criticisms and expectations help push and improve those art forms.

It’s how those art forms develop and evolve.

For instance, it’s rare that a piece of cinema can be produced without any real knowledge of the medium of cinema (exhibiting the poorest displays of directing, acting, and editing), and yet still win awards simply because we liked the idea behind the plot. Or that a song can reach the top of the charts when executed by a musician who has no musical ability whatsoever, simply because we like the sentiment being expressed in the lyrics.

For most art forms we demand both parts of the equation: a likable, poignant, or relatable subject matter…..AND masterful, insightful execution.

But not with photography. If a photographer merely chooses the right topic, they’re rewarded for it instantly, and without application of any serious, structural standards at all. As long as they “point” their cameras at the right subject matter, their work is celebrated.

Not just by the masses, but by even our most important societal institutions.

And this practice is not only patronizing to the individual artist, it’s also condescending toward photography itself, as it sends a signal that this medium isn’t taken as seriously as other mediums that do inspire more rigorous standards and criticism.

Part 4: Photographers Using Photography

Ok, in order to counter the genres of photography highlighted at the start of this article, let’s now examine some works that combine compelling content with photographic expression, works from photographers who use this medium to extract an insight or an aesthetic from their subject that perhaps only the medium of photography could have extracted or unlocked.

To begin, let’s first examine some of what we refer to at ASOP as ‘first level,’ photographers, or foundational photographers. These are photographers who choose one specific property of the medium to explore, and then spend the majority of their careers exploring it. And in doing so, they often lay the foundations for others to follow, providing insights into what that one single property of photography can bring to the table.

In other words, these photographers are not practicing the medium at its pinnacle of complexity, rather, they’re practicing it at its most fundamental ground level. They’re taking individual photographic techniques (like the ones we applied to the collage experiment above), and they’re testing them, one at a time, upon subject matter that they find compelling.

So with that in mind, here’s photographer Fan Ho exploring the way photographic choices can be used to alter our perceptions of the LIGHT within a given scene:

…and in doing so he shows us a world, or an aesthetic, that we wouldn’t otherwise be able to perceive with our own eyes. A world that can only be unlocked through the capabilities of photography

Next, here’s Richard Avedon exploring how TIMING can render a human figure in positions that were impossible to hold and to perceive before the advent of photography:

Next, here is photographer Alexei Titarenko exploring how very long exposures can render the PASSAGE OF TIME in ways that can’t be perceived by the human eye. To illustrate this, he exposes foot traffic on a public staircase for minutes on end, reducing the collective humanity to a cloud of rubble, with the only remaining hint of any individual person’s presence being the occasional hand placed upon the banister rail:

And finally, here’s Victor Schrager exploring the ways in which focusing on alternate LAYERS OF SPACE can allow his lens to soften or abstract an image into a sight that couldn’t easily be experienced through typical human perception.

This last image somewhat mimics the form of an impressionist painting (or even a De Stijl painting), or again, it “borrows its syntax” from those kinds of paintings, however, very importantly, we’ve arrived upon this result using photographic methodology, as opposed to making an actual De Stijl painting and then doing ‘copy work’ of it.

So each of these photographs is what we at ASOP call a “first-level” photograph, in that each seems to be working to explore one single property of this medium. And that kind of exploratory photography often provides a fountain of insights about how these most fundamental elements of the medium can be used.

So again, we’re talking about first-level exploration here. These photographers are establishing the basic “building blocks” of the medium.

But most of these images are also highly abstract.

And the reason these particular examples are abstract is because first-level photographers tend to be pushing the boundaries of what one single technique can accomplish, so that they, and the rest of the photography community, will now forever know those boundaries.

And this means their efforts produce compelling images, yes, but just as importantly they also produce insights (or building blocks) that can benefit other photographers. Because in finding the boundaries of each of these techniques, it allows future photographers who study their work to skip over that particular exploration, enabling those that follow to INCORPORATE those insights into the next level of exploration, and to begin building more complex images that were unforeseeable in previous generations.

That’s how a medium develops and becomes increasingly more complex, more versatile, and more useful…as opposed to flatlining and becoming totally stagnant.

And then once those core properties have been explored and digested, the next level of photographers is then free to pick and choose and COMBINE those properties until they’ve arrived upon a more dynamic and more unique personal style, so that they can convey the world through a set of images that can only be achieved - or even imagined - through the unique properties of photography.

And at that point, photographers can then produce images that are far less abstract, ie: images whose value tilts more toward the subject itself…but while still ensuring that their work holds a substantial photographic merit, thus qualifying the work to represent photography as a fine art.

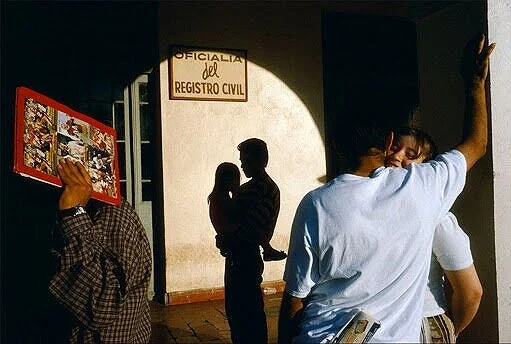

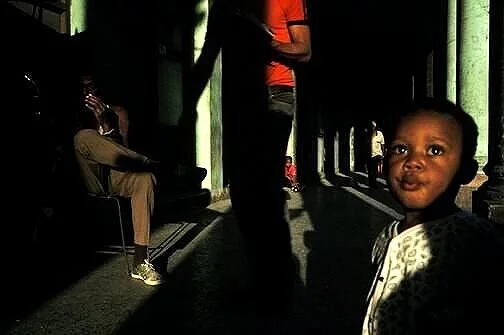

As an example of such a photographer, let’s look at the work of Alex Webb, who has used his career to explore combining LIGHT differentials with disparate layers of SPACE within the same shot, in order to form a very consistent aesthetic:

Alex Webb

Alex Webb

Alex Webb

Alex Webb

In each of these shots you can see he’s hunting for different layers of space that are also lit very differently. And when he aligns his scene in this way, he has placed multiple photographic variables in front of his lens.

So as was the case with our collage experiment, he knows that this will allow several options for how he can render the final image, depending on how he chooses to use his camera to capture it (ie: he can mix and match different decisions regarding exposure, focus, compression, and timing). Which makes his specific choice of image a product of his own unique preferences and creative vision, as well as a product of the unique capabilities of photography.

Or to put it another way, once he has aligned his scene this way, he knows the same subject matter can be expressed in different ways, which makes his choice of expression a statement of his PHOTOGRAPHIC AUTHORSHIP.

Further, and probably more to the point, Alex Webb has used his craft here to create a world we can never actually experience through normal human sensory perception. We can only experience this world through his images.

In other words, had you been standing next to him when he was taking these pictures, this isn’t how your eyes and brain would have perceived these scenes. It has taken the well-studied properties of the medium of photography to generate this portrayal of the world.

In short, these images are not recordings of the world, they are expressions of the world. The insights we get from them come from the way the medium of photography was used…they don’t come only from the subject itself.

By contrast, the images discussed at the top of this article are comprised entirely of ideas and aesthetics that we CAN experience and appreciate with our own senses - even had photography never been invented - so long as we were standing in the same spot the photographer had been standing, and we were looking at the same thing.

Moreover, in each of those images, the subject matter speaks entirely for itself. The medium of photography has not been used in any way to express something about that subject, or to describe that subject, or to comment upon that subject…the medium has merely been used to record - or to ‘show us’ that subject.

But Alex Webb’s process certainly isn’t the only approach, here. So let’s explore some others.

If it is the case that a photographer remains adamant that their images not abstract or diverge from what’s in front of their lens, and that they’d rather build a scene and then merely record what they have built, then it would be difficult for the work to have any strictly photographic merit unless the sculpture or scene they’ve built was crafted using a lot of photographic properties and/or expertise.

In other words, instead of hunting for photographic properties that are naturally occurring in the real world (as Alex Webb is doing), some photographers prefer to GENERATE those photographic properties within a studio setting.

As an example of what that might look like, let’s examine the work of Gregory Crewdson, who uses full-scale cinema crews to create and light an entire scene, which he then uses for still photography, rather than for cinema:

Gregory Crewdson

Gregory Crewdson

Gregory Crewdson

Here Crewdson is not doing a whole lot with his camera to abstract the image from what was in front of him, meaning that if you were standing next to him while he was taking these pictures, this is more or less how it might have appeared to your own eyes (minus a bit of post-processing). But at least the scene he’s created, the literal THING he’s built in front of the camera, has been sculpted using photographic properties, such as the lighting dynamics he’s generated, and the spatial layering he has choreographed.

In other words, instead of seeking out naturally-occurring photographic properties in the real world and then choosing to “capture them one way as opposed to another” (as Alex Webb does), he’s doing the opposite, he’s designing or engineering photographic phenomena, EXTERNALLY, so that those phenomena might pass through his lens in one way as opposed to another.

Thus there’s still some photographic authorship being demonstrated here - some discriminating choices he’s making based on his photographic expertise - but those choices have been made externally, in the design of his scene, rather than being made internally, through the mechanics of his camera system.

And this means that while the sculpture he’s made does contain more of the work’s merit than the picture that records it, that sculpture at least required substantial knowledge of photographic properties in order to create it. And while he may not be using his camera to express very much here, he is still providing other photographers with ideas and insights as to how they might be able to use these properties in future endeavors.

Which means his images play some role in expanding this medium. They push the discourse on photography a little bit further.

And for one last example, let’s examine the work of Philip-Lorca DiCorcia, who appropriates familiar commercial photographic syntax into his fine art photographs:

DiCorcia’s work can be interpreted in several ways.

Some see it as poking fun at the commercial techniques that we so routinely encounter in advertising photography (for instance, instead of applying commercial lighting to a fashion model, he applies it to a church service, or to a real estate transaction, or to a lonely housewife). Others see it as a more serious attempt to diffuse the effectiveness of commercial photographic strategies, by appropriating them and applying them toward alternate subject matter, because doing so undermines and dilutes the associations that commercial photographers have spent decades trying to build.

Either way, his imagery takes familiar, already-established photography syntax and then turns it on itself.

What do we mean by “well-established syntax,” exactly?

Well, once our public gets used to seeing a widespread and repetitive photographic methodology on a very routine basis (ie: specific configurations of photographic decision-making), we begin to associate those structures - or that “syntax” - with very specific ideas.

For instance, most of our public has come to recognize the way certain lighting techniques tend to look like “advertising” photography, even if they can’t put their finger on exactly why. Or the way certain kinds of grainy, black & white, documentary images look “gritty” and “serious,” as opposed to “upbeat” and “light-hearted.”

And once these associations have been developed, photographers have several choices for how they can then make use of those associations.

For instance, one option is that they can choose to utilize and exploit pre-established cultural associations, in order to achieve a more emphatic punctuation to their images.

An example of this approach might be when the public gets used to seeing documentarians shoot grave, human struggle with a “grittier” sensibility, and then from there on forth, whenever a documentarian shoots scenes of human struggle with that “grittier” sensibility, it reinforces the idea that the circumstances being depicted in the photographs are, indeed, very dire.

Again, that would be an example of a photographer exploiting “familiar photographic syntax,” or exploiting well established methodology.

A second option, however, is that photographers can build upon cultural associations that have already been established, not by using an already-familiar construct, but instead by extrapolating the logic that originally lead us to those familiar constructs, until they’ve hit upon an even more effective method, perhaps one that better taps into those very same cultural associations.

But a third choice is that photographers can choose to do the exact opposite. They can choose to contradict the viewer’s expectations, or to undermine an established methodology.

An example of that approach would be if a photographer chose to use that same “gritty” style mentioned above, but applied it to kindergarteners having their afternoon snack. Doing so might foster a sense of irony, or just a different kind of narrative insight. Or, if used widely enough throughout our culture, it might undermine the effectiveness of that specific construct.

And so considering the wealth of visual syntax that already exists within our culture, it means we now have a potential “language game” on our hands.

We get to “play” with established photographic syntax.

And in the works above, DiCorcia is doing something closer to that third approach; he’s using the associations we have surrounding “commercial” imagery to depict subjects and scenes we wouldn’t normally see in advertising photography.

And this makes his work a particularly important case study here, because he’s essentially playing that very “language game” we’re describing.

But just to elaborate a bit further on exactly what we mean by “language game,” the main idea to grasp here is that we’re now at a point where photography has been used widely enough throughout our culture — and has developed enough cultural associations around repetitively-used constructs — that photographers have been presented with something of a “game,” …..and one that has several moveable pieces.

If photographers choose to “package” a given subject in one particular kind of expression, then the viewer will likely perceive that subject (and the message of the photograph) in one specific way…..whereas if they package that same subject in a different photographic syntax, then the viewer will likely perceive that same subject (and the message of the photograph) in a very different way.

And it’s in configuring those pieces — it’s in configuring the subject matter in relation to a specific photographic grammar and syntax — that meaningful expressions can be fostered.

And it really needs to be emphasized here that developing a more complex ‘photographic language’ is the biggest and most coveted prize in all this, because once a strong photographic language has been established and familiarized within our culture, that language can then be tweaked and expanded, or subverted and undermined….all of which opens up infinite new directions and pathways for this medium to grow.

In other words, we can’t use a photographic language, until we’ve established and built a photographic language first.

Which means the far, far greater indictment of the ‘copy work’ stye of fine art photography is that it does exactly nothing to expand the medium of photography, or grow the “language of photography” at all.

So once again, to be as clear as humanly possible:

The most popular style of fine art photography — ie: the style that dominates the walls of every contemporary gallery, as well as the pages of every contemporary fine art magazine ……that style….. in addition to recording rather than expressing, and in addition to requiring no substantial knowledge about photography whatsoever, AND in addition to being a protocol that was designed by 'copy work’ engineers in order to prevent photographers from expressing themselves in any way..……on top of all of that…......that style of photography also doesn’t move the needle at all in terms of developing or expanding our photographic language.

In fact, the prevalence of that style is actively keeping this medium more stagnant.

And it is in this particular way that the widespread celebration of the ‘copy work’ style of fine art photography does the most harm.

And moreover, it is for this particular reason that it’s so baffling that it continues to be the style of photography endorsed by seemingly every art critic and every MFA professor across our culture.

But returning to these three photographers here for a moment, if Webb’s work requires a profound understanding of the physical properties of medium, so that he can quickly recognize those properties and manipulate them on-the-fly in the real world…..….and if Crewdson’s work requires a profound understanding of those same physical properties, not so he can “capture” them through-the-lens, but so he can instead stage and align those physics in front of the lens…….…then DiCorcia’s work requires a profound understanding of photographic syntax, and the associations the viewing public might have in relation to that syntax.

In other words, in order to do what they do, all three of these photographers needed to have studied and mastered some crucial aspect of this medium, and they’re now using the expertise they’ve acquired in order to advance the medium of photography into something more sophisticated than it was when they were first learning it.

They’re growing the medium. They’re pushing the medium. They’re contributing to the medium’s evolution.

Absolutely none of which can be said of the photographers at the start of this article. All of whom have confined themselves to shooting images that require no substantial knowledge about the medium at all (either physically or syntactically).

Further, in each of those earlier photographs, we were viewing something that the human mind can experience, and can conceive of, without the medium of photography ever having existed at all.

Which means not only are we not seeing any advancement of the medium itself, but we’re not even getting any kind of new insight, ie: an experience or perception that could only be experienced or perceived through the medium of photography.

And if you’re going to represent yourself to the world as a photographic artist, your work should probably do at least one of those things.

Your work needn’t always be about exploring and advancing the medium, but if that’s the case it needs to at least be about using the medium. And if your work does neither of those two things, then we probably need to classify your creative skills as something other than photography, and concede that you are merely using your camera to record, or render ‘copy work,’ of another artistic medium.

Part 5: The Calcifying Preferences of the Art World

These last few entries seem to beg the question, “Well ok, so what? Clearly there are photographers out there who are using this medium for its own merits.”

Of course there are. The problem is that those photographers represent a shrinking minority within the fine art community, while the photographers at the top of this page represent a fairly dominant and quickly solidifying majority.

For those who frequent the fine art gallery scenes in places like New York and London (ie: where the major financiers, power brokers, and “tastemakers” convene in order to govern the direction of art photography), and for students enrolled in photography MFA programs, those first two genres have become the ubiquitous norm.

And in those circles, photography continues to be the only well-established art medium for which merely CHOOSING a subject is all that is required (photographers routinely mistake their choice of subject matter for being the medium itself).

But as we’ve already demonstrated, a photographic subject can be addressed in a variety of unique articulations.

Because between the subject and the camera’s sensor….. an “image” has to pass through several mechanical devices, and hundreds of potential intellectual choices, until what ends up on your sensor is drawn from the subject in front of it, and inspired by the subject in front of it, but the merit of your image ISN’T the subject in front of it. The merit of a fine art photograph — as is the case with any art form — is how you’ve used the medium in order to uniquely express that subject.

Yet, many of our most prestigious art institutions, from notable MFA programs all the way to major international art summits like the Whitney Biennial, don’t seem to require photographers to address their subjects at all.

We simply stand before the photograph, and we critique their choice of subject.

This means that fine art institutions around the world are routinely exhibiting photographs that have been authored identically, using the same formulaic, neutral construct that is designed merely to show us the subject, rather than express the subject.

And even if one can manage to overlook the identical authorship in most of these pieces, or even if one simply does prefer to value the subject matter itself, exclusively, perhaps the greater frustration here is that, in many of these photographs, the subject was likely more profound and more striking if one were to have actually encountered it in real life.

For instance, the live human beings wrapped in plastic, or a naked young woman with a live coyote wrapped around her neck…those subjects would likely have been more moving and dramatic had we been there in real life to witness them in person, which is to say that, if anything, the photograph is a second rate version of the sculpture that it’s recording.

Or, to put it another way, there’s a reason that people still line up by the thousands to see Michelangelo’s ‘David,’ in person, despite the fact that they’ve seen countless photographs of it throughout their lives. Simply put, it’s because the statue itself contains more insights than a single piece of copy work that records it. And the general consensus is that viewing a single, neutral photograph of David just “doesn’t do it justice.”

And it really has to be said that if a subject is LOSING insight and value in its transformation from real life to photograph — ie: if the subject itself was more insightful than the photograph that’s been taken of it — then to present that ‘loss of value’ as a paramount example of fine art photography is nothing short of a baffling insult to this medium.

If one is to call oneself a “photographic artist,” it's probably fair to expect that something be GAINED as a subject or scene passes through one's lens, whereby the content of the photograph (in passing through the properties of the medium and the choices of the photographer) undergoes a profound transfiguration, as the photographer builds an insight from, or sculpts something out of, the scene that was in front of them.

To put it another way, if one were to seek out the exact subjects and scenes that were shot in the preceding section (Fan Ho’s gondolier, or Titarenko’s public staircase), one would be roundly disappointed by the real-life appearance of those scenes, because in each of those cases, the photographic image that the artist created was something GREATER than the scene itself.

Because the photographs of those subjects contained more insights than the subject alone.

Part 6: The Problem Originates in Art School

That it is photography's own champions, and often its most famous practitioners, that play the most central role in neutralizing and disempowering this medium, as they discard photography’s greater capabilities in order to use their cameras as a mere ‘scanning device’ (and one that works only to promote OTHER kinds of creative acts)….is one of the strangest paradoxes of the art world.

That it goes largely unnoticed is perhaps even stranger.

And that so many photographers spend years of their lives (and a personal fortune) on gaining an MFA in photography without ever even exploring their own medium’s substantive properties, is maybe strangest of all.

In fact, one can routinely encounter photography MFA’s who don’t seem to know much of anything at all about how photography works (either in terms of its physics, or in terms of its powerful semiotic abilities), simply because their own professors either didn’t understand, or didn’t value, the more complex properties of the medium.

And perhaps the most disheartening development to emerge from all of this is that, anecdotally, many of those photographers are really quite proud of that ignorance. They wear it like a badge, frequently echoing the famous words of Annie Leibovitz and declaring “I’m not a TECHNICAL photographer!”

And the problem with that statement, of course, is that it’s just factually untrue, in the same way that anyone who proclaims, “Oh, yes, I speak English… I just don’t use any of your ‘nouns’ or ‘adjectives’ or ‘prepositions.’ I’m not a GRAMMATICAL speaker!” …is also factually incorrect.

All speakers of language are grammatical speakers, whether they’re aware of it or not, and all photographers are using the technical properties of photography, whether they are aware of it or not.

In the same way that every painter chooses to use one technique over another, whether it be a brush stroke, or a dab method, or a splatter method…all of those methods are different techniques. Photography is no different. Every photograph that has ever been made is a “technical” photograph, in-so-far as the person who made it chose to use one technique over another, or chose SOME configuration of these technical properties over another.

It’s just that the art school students who make such proclamations have been taught only one technique, only one configuration of these properties, and they stick to it exclusively, using it over and over again like a formula.

So what those photographers are really saying is that they’d just prefer to remain unconscious, or ignorant of photography’s richly diverse methods of expressing.

They want to remain illiterate to the language of photography.

And, quite ironically, what they think they are saying is “Don’t box me in with your rules! Don’t turn my ‘art’ into a ‘science!’”

But the irony of that reaction is that it actually works to achieve the exact opposite effect; they actually become even more boxed-in to a very narrow understanding of the medium, which, in turn, prevents them from expressing their own creativity more uniquely and more effectively.

Because if the primary components of fine art photography are: 1) the subject that’s been chosen and 2) the syntax or construct that’s been used in order to express that subject…. then those students have been boxed into expressing every subject they want to shoot in the exact same way, which leaves them ONLY their choice of subject matter to use in order to differentiate themselves.