The Problem of Mass Production in Photography: why Canon, Sony, and Nikon are not our friends.

The Preamble:

In our other case study, (The Art World's Mishandling of the Medium of Photography) we explored how higher-minded institutions – such as the fine art world, and the photography programs at major colleges and universities – have impeded the development of this medium by elevating subject selection, and the development of non-photographic talents, above the actual medium itself, and how, in doing so, they’ve neglected to teach this medium's higher capabilities to the very people who will go on to shape and champion the medium throughout the next generation.

This page will be used to examine the other great navigator of this medium: the “photo industry.”

For the purposes of this discussion, the "Photo Industry" will encompass two separate but related groups, each wielding a mighty influence over the direction and development of this medium.

First, we have the companies that design and manufacture our tools and equipment, such as our cameras, our lenses, and our software applications. Examples of such companies would include Canon, Nikon, Sony, and Adobe.

And second, we have the professional photographers who use those tools and applications in their day-to-day occupational tasks, such as wedding photographers, sports photographers, food photographers, and portrait photographers.

In short, instead of examining the impact of the intellectual and academic communities on the development of this medium, we're going to be discussing the impact of the commercial photography community – ie: the camera companies, and the "pros” – who together serve as maybe the most prolific gateway between this medium and the general public.

What we will discover here is that, if the fine art community has mis-navigated this medium on a more theoretical level, ignoring photography’s higher capabilities and stifling the growth of photography as a visual language, then the photography “industry" has mis-navigated this medium on a much more practical level, by abstracting the technical processes of photography into a limited, closed-circuit framework of proprietary technology, one that allows companies like Canon and Sony to control the very manner in which photographers both practice, and understand, their craft.

Companies like Canon, Sony, and Nikon are “consumer electronics” companies first and foremost, which means the key dilemma facing occupational photographers is that they practice one of the very few forms of professional expertise that sources its tools - and its methodologies - almost exclusively from a consumer marketplace.

And knowing this is the case, these companies design their photographic tools in ways that are not always efficient or even particularly beneficial to us, but rather in ways that are simply more profitable to themselves within that marketplace.

And they accomplish this, primarily, by designing cameras that coerce photographers into a dependency on their own proprietary “solutions,” as well as a dependency on their own unique operating systems and terminology, because they know that doing so will breed a far greater brand-loyalty among the people who buy their cameras.

For their part in all of this, we’ll find that “pro” photographers have fallen into the trap of blindly trusting the “solutions” that these companies are peddling, while building almost their entire understanding of photography - and their entire professional approach - around those tools and solutions. Moreover, they form almost all of their industry “jargon” and nearly all of their professional “culture” around those proprietary solutions as well.

And so whereas the professional photography community should be positioning itself as a counter-balance, forming a more adversarial relationship that might keep these companies in check, while simultaneously pressuring them into designing tools that allow for more efficiency in operation, or even just tools that EXPAND the complexities and possibilities for how they can shoot…. instead, as things currently stand, we have the opposite.

As things currently stand, Nikon/Sony/Canon design technologies that limit photographers, in fact, technologies that corner photographers into using a lot of ineffective methodology….and then our industry “pros” not only embrace those ineffective methods, but they maintain a baffling and enthusiastic loyalty toward the very companies that are boxing them in.

Introduction: A Tale of Two Methodologies

To illustrate the problem at hand as concisely as possible, I’d like to begin by comparing two very distinct batches of contemporary wedding photographs.

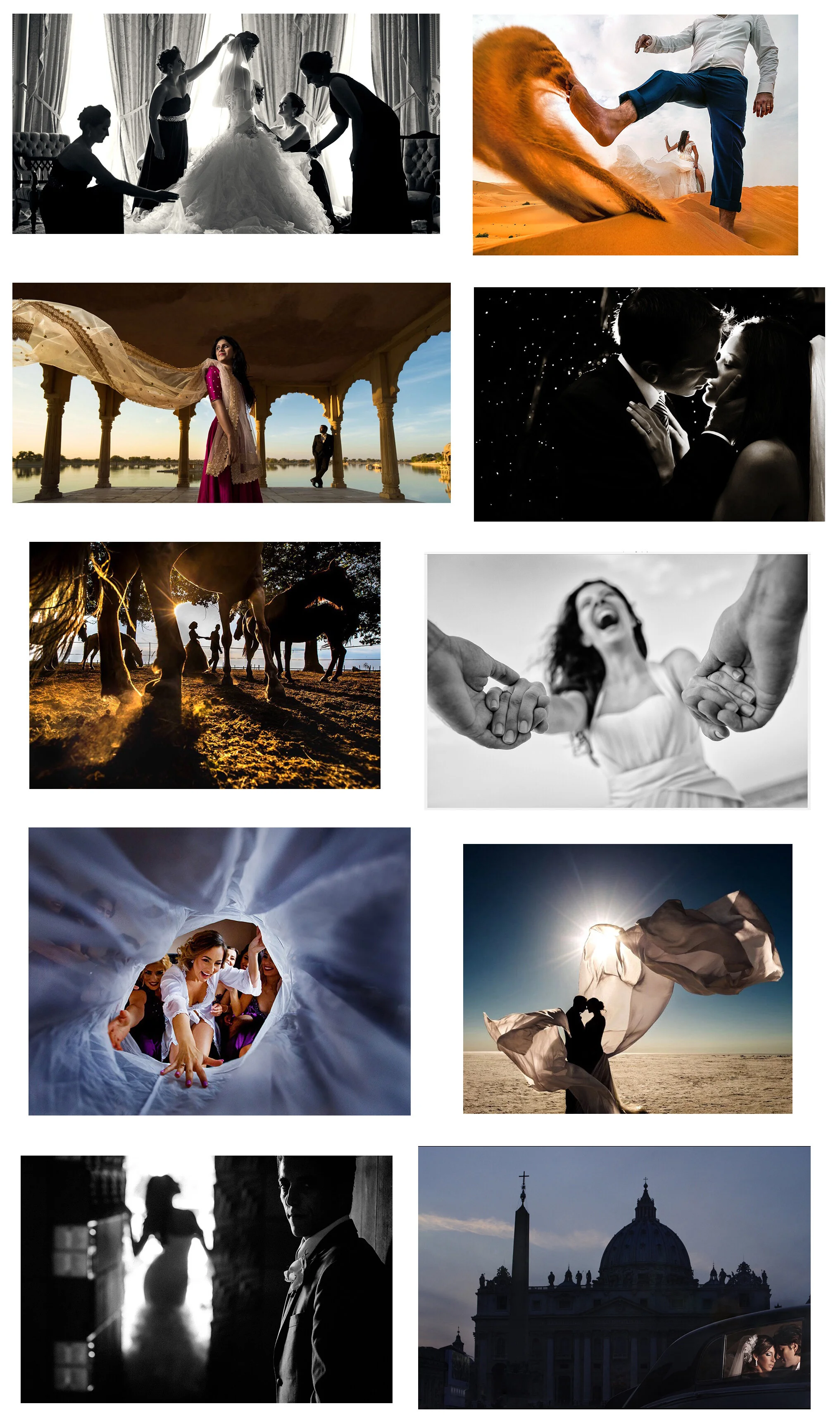

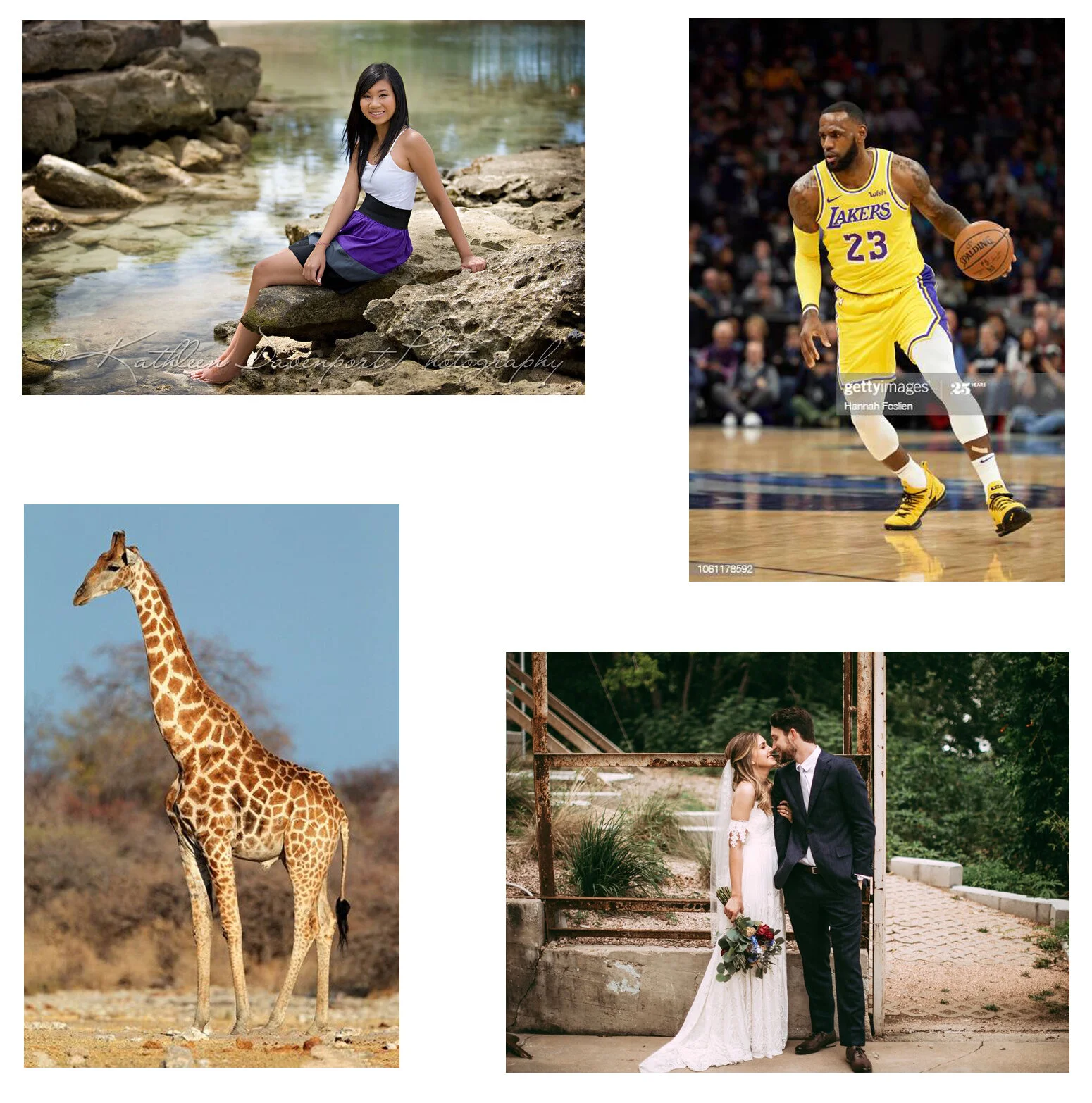

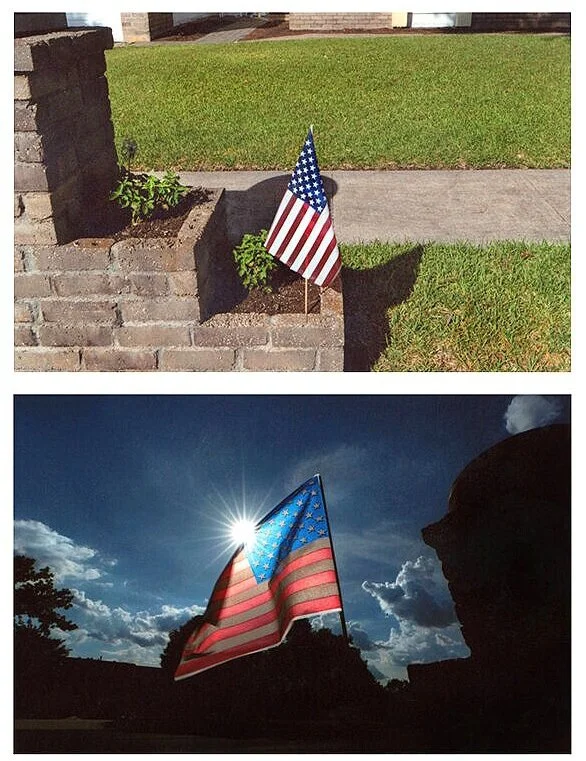

First, let’s have a look at batch #1:

I’ll start by noting that there’s nothing particularly wrong with any of these images. They get the job done.

In fact, all are fairly typical for the wedding industry, which means if you have wedding pictures of your own, there’s a very good chance they resemble these here. So you might consider this batch to be something like “the industry standard.”

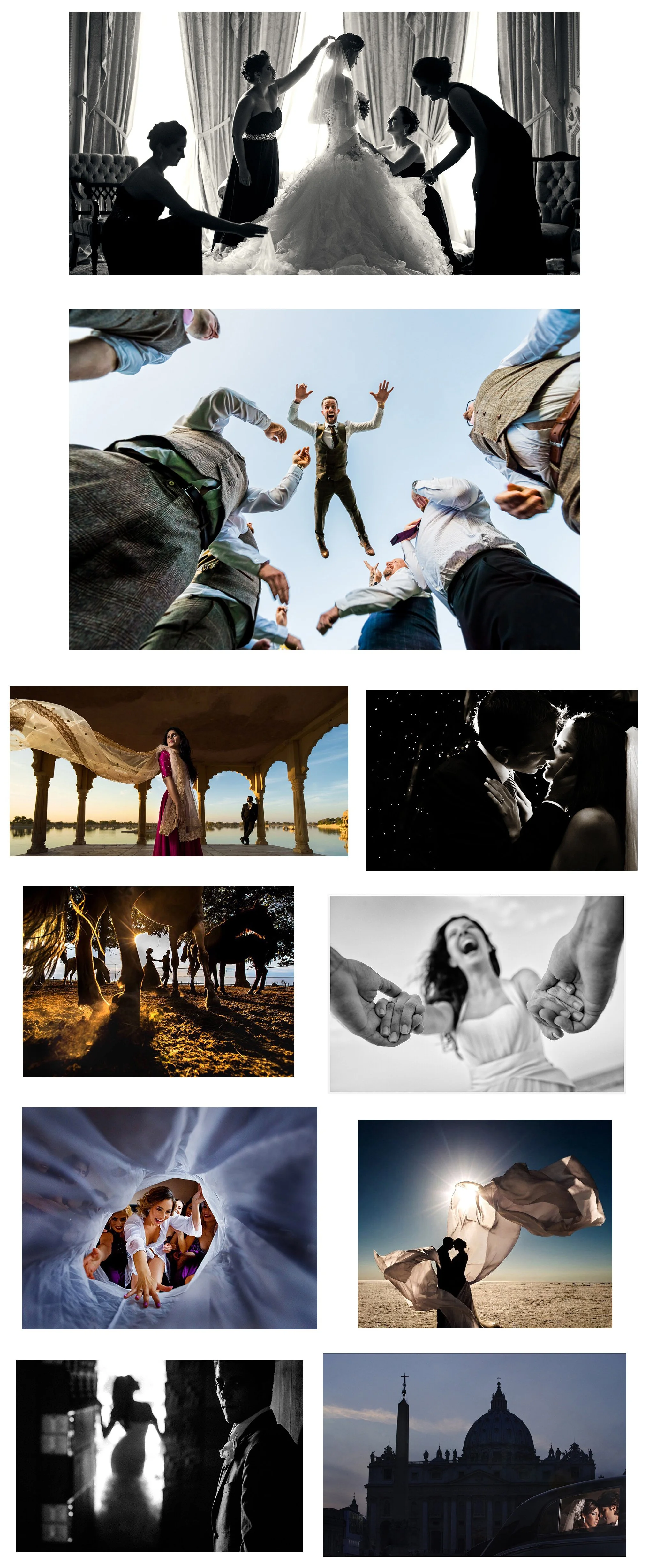

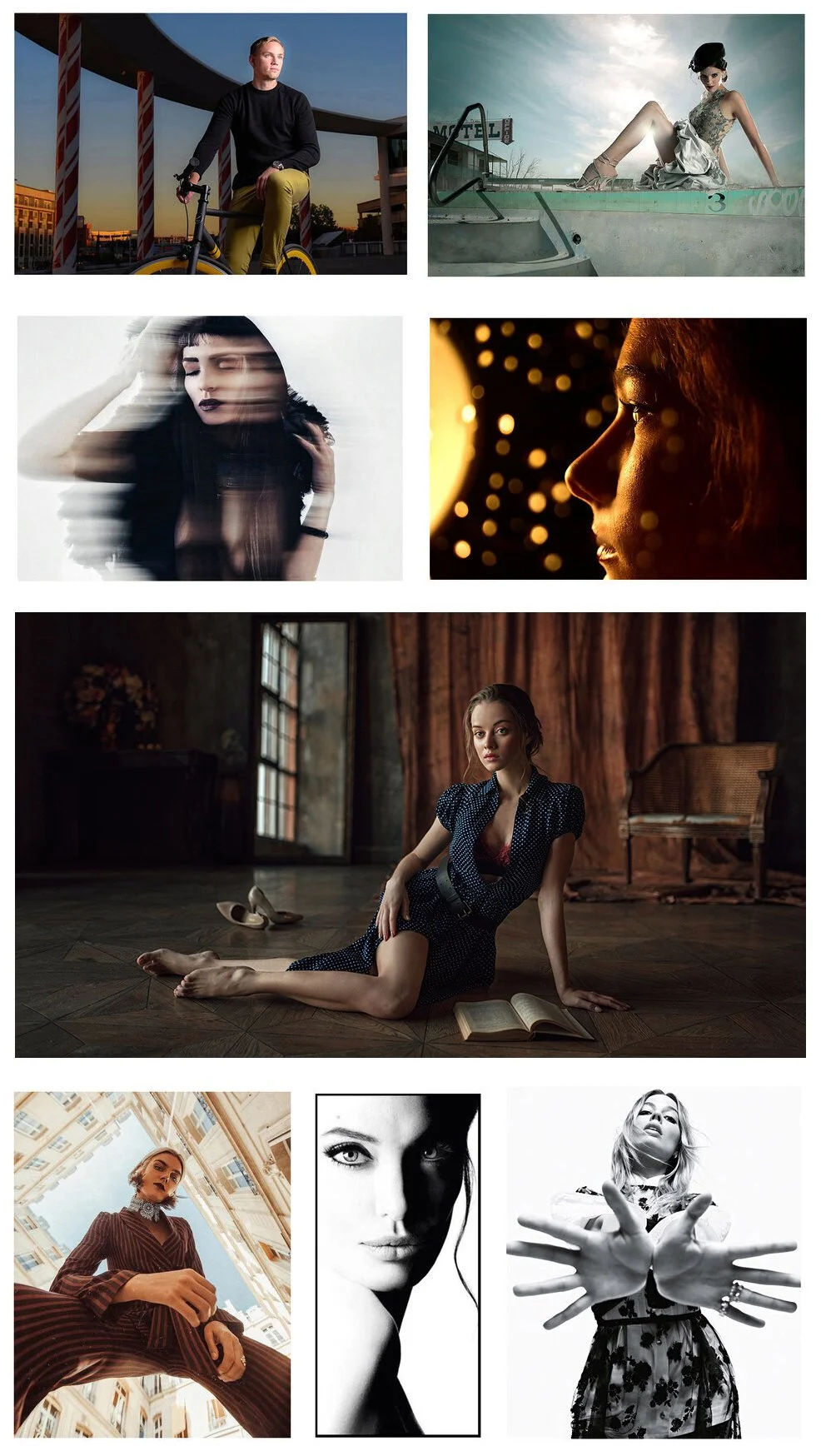

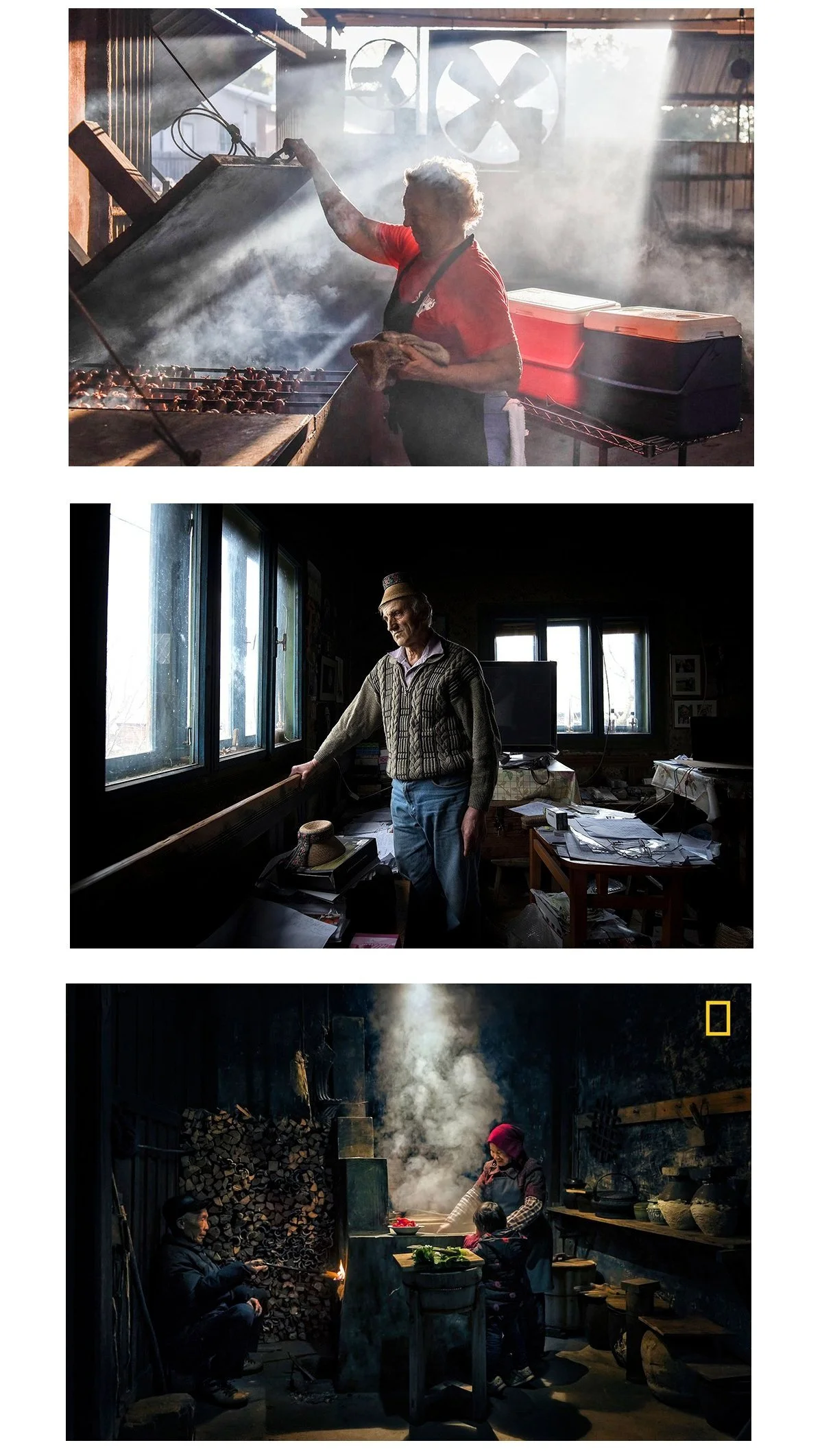

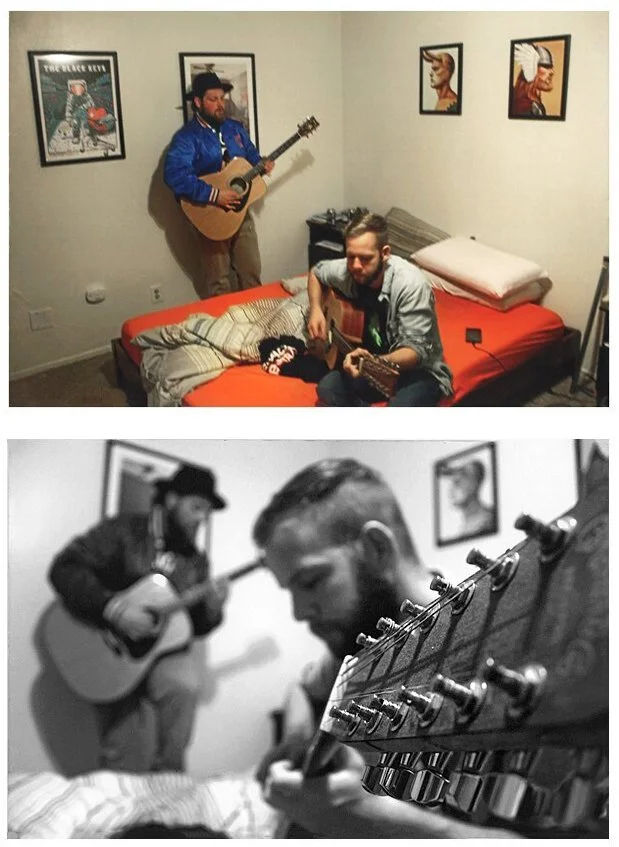

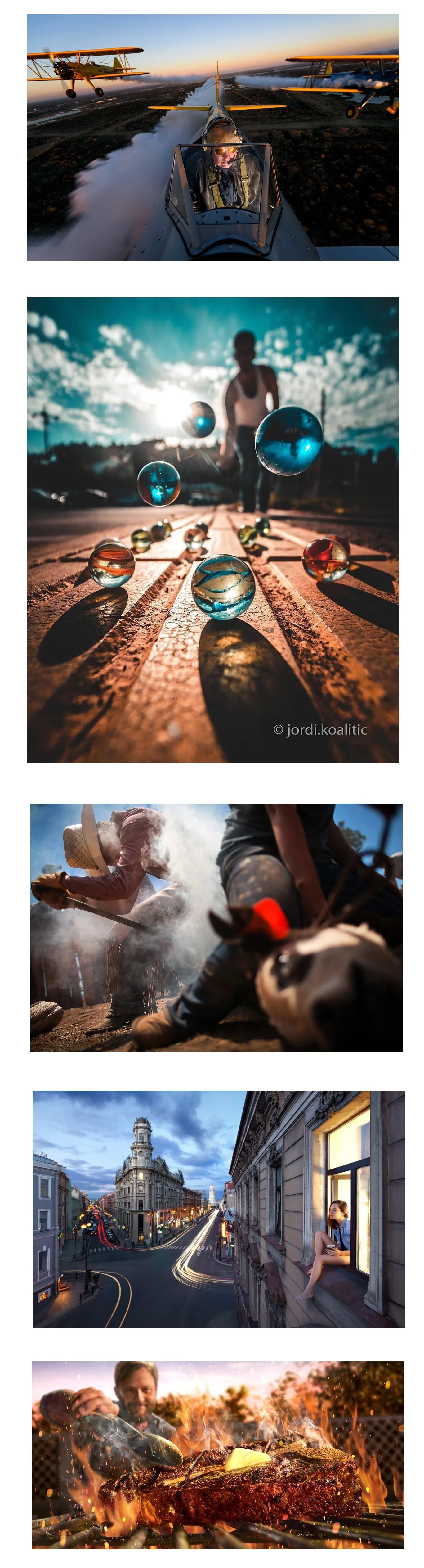

But now here’s batch #2:

This second batch is not as typical, which is to say that relatively few people have wedding pictures that look like these. And because of that we tend to say that these images are a bit more remarkable, or rare, or that they impart a more vivid narrative energy….or that they’re more cinematic.

In other words, we tend to think of these as rising above the “industry standard.”

But what, specifically, is different about them?

Well some might posit that these latter images have been taken by more notable, or higher earning photographers.

Which is true. These pictures have all been culled from the portfolios of internationally award-winning photographers. In fact, it might even be the case that only one or two wedding photographers in your region produce this kind of work with any regularity, particularly if you live outside the largest and most competitive markets, such as New York or Los Angeles.

However, notoriety and earning power are consequences of this type of shooting, not the other way around. So that assessment says nothing of what these photographers are actually doing differently.

If pressed, and without the relevant technical vocabulary, in my experience the layperson will often reach for more qualitative explanations. For instance, they’ll say the latter group of photographers is simply more “talented,” or that those photographers have a better knack for capturing the right moments, or that they have some “intangible photographic eye.”

But the purpose of this essay is to clarify that the factors distinguishing these two groups of images are a lot more concrete than most people realize, and have little to do with the photographer possessing any kind of mystically innate talent. This has more to do with the way a photographer has been taught to understand the medium, and the technical approach they take to their shooting.

And the formulaic simplicity of that first batch is due, in large part, to the ways Canon/Nikon/Sony have designed their equipment, and how they’ve encouraged photographers to practice and understand the medium using that equipment.

Because the technical “solutions” (the camera features) that these companies have designed are very limited in what they can do.

And therefore in convincing the public that these proprietary solutions are not just one limited shortcut to getting some fairly simplistic images — but rather, they’ve convinced the public that their own proprietary solutions ARE the very fundamental skills that every photographer should be learning — these companies have condemned a lot of professional photographers to a relatively small and mediocre subset of what can be accomplished with a camera.

Specifically, they’ve incentivized photographers to select shots based on what they know their camera’s algorithms can handle, rather than to select shots based on the most poignant or most sophisticated result their scenes might allow.

Or in short: professional photographers have reversed the flow chart on how to take pictures, to where, instead of adapting their process to fit their own creative vision, they do the opposite, they adapt their eye toward seeking the predetermined shots their technology was programmed to take.

And it’s absolutely crucial to note that this assessment doesn’t apply solely to the camera features that are marketed as “fully automatic” functions. This actually applies even more-so to the “advanced features” of a modern camera, the ones most pros have come to depend on (the histograms, the metering modes, the hdr compilers).

Because underneath every one of those seemingly sophisticated features is a set of algorithms and engineering decisions that opaquely governs (and limits) the framework for how an image is captured and understood. And in my experience, few photographers actually understand the logic of what’s happening underneath the interface of their cameras.

So returning to the question, “What SPECIFICALLY is different about these two sets of images?”

Well, the most tangible difference is that the photographers who shot the first batch have been implicitly taught to avoid any physical variables in their scene that might confuse their camera’s pre-determined response systems. And to that end, they’ve composed a shot that has no significant lighting differentials, no heavily disparate layers of space, no moving subjects (ie: they’ve been taught to compose a simplistic, “one size fits all” kind of scene) …. so that their camera’s algorithms won’t become confused. Because doing so will allow them to use all of the engineered camera features they learned about in their workshops and tutorials, and all without any real fear that those camera features will keep “messing up.”

And as a side note, in my experience these professional photographers aren’t particularly aware that this was the logic behind the methods they were taught. More what happened is these methods were selected for them, paternalistically, by those within the industry who’ve connected the dots between the fallibility of a camera’s algorithms and the methods that best neutralize those fallibilities.

And then by the time it all trickles down to aspiring professionals and newcomers, these methods are authoritatively sold to them as “the industry standard” or “what most pros do,” and furthermore, it’s all been tightly wrapped in a package of esoteric-sounding technical jargon that it now has the unquestioned veneer of technical legitimacy.

But on the flip side, the photographers represented by that second batch are much more familiar with the underlying properties of photography (as opposed to just their camera’s interface), which means they can intentionally hunt for different amounts of light, different layers of space, different kinds of movement, etc., and then, rather than fear those variables - rather than avoid the actual photographic assets of their scenes - they can USE those properties in order to structure and punctuate their images.

So that’s the primary difference between these two batches of images.

But the key problem here is that this latter approach is practiced by only a very small segment of the professional community. The overwhelming majority of professional photographers that I encounter demonstrate little-to-no substantive knowledge regarding the underlying workings of photography, and have instead learned this medium entirely through the abstraction of features and functions that have been built into the their camera’s interface.

Which means their entire understanding of this medium comes through the translation of photography that Canon, Sony, and Adobe have given to them…which, in turn, gives a lot of unquestioned power to these companies regarding the public’s perceptions about “how photography works.” And moreover, it also allows these companies to push for methodologies and industry standards that are simply more profitable for themselves.

And then finally, in addition to building their methods around such technologies, most pro photographers then also use their authority and reputation to perpetuate these methods, en mass, through the advice they impart to emerging hobbyists and aspiring professionals.

So at the end of the day we’ll find that much of the ‘conventional wisdom’ we get from the photo industry actually puts very defined limitations on those who follow it, which makes a lot of it really bad advice.

And despite what many professional photographers seem to believe, it doesn’t take an extraordinary amount of in-born talent, or an advanced degree in mechanical engineering, to be able to produce more versatile and more sophisticated results.

In fact, it’s just as easy to learn how to exploit photographic variables as it is to learn to avoid them.

The problem is - and here’s the rub - it’s far, far more profitable for Canon/Sony/Nikon that photographers remain hooked on their own proprietary solutions. And to that end, they’ve designed their interfaces and operating systems in ways that often coax, trick, and strong-arm photographers into using those solutions. And moreover, they use their far-reaching market presence, and their vast networks of workshops, tutorials, and product representatives, to sell photographers on the idea that their own technologies and algorithms are the best path to better images.

Whereas, on the other side of this issue, there is no equal and worthy adversary to counter their arguments, no robustly-funded and well-organized effort that might caution the public against such methods, which means that the companies who comprise this powerful Photography Industrial Complex get to enjoy the lone voice on the matter.

So to summarize this entire dilemma:

Our ‘Industry Standard’ for professional photography has been vastly oversimplified – “dumbed down” if you will – in order to accommodate the grossly inefficient, but highly-profitable technologies that camera companies prefer to sell…..and to my observations, most professional photographers aren’t particularly even aware of this dynamic.

In fact, it’s all rather quite the opposite.

Most professionals whole-heartedly believe that it’s in using these very technologies that their expertise is legitimized, because, quite ironically, they think that mastering their camera’s most esoteric features is what will make them more advanced and more knowledgeable shooters. They’re so caught up in the thrill of speaking an exclusive language of insider’s jargon, and racing their colleagues to the newest technologies, that they haven’t stopped to notice that the vast majority of the tech that these companies are producing actually benefits those companies far more than it benefits them.

But ASOP’s entire schtick these past 10 years has been to take common, ordinary citizens, almost none of whom identify as being abnormally “talented” or “mechanically inclined,” and enabling them to take the kinds of pictures exhibited in that second batch within only a few months of starting. And the reason we’ve been able to do this is because we demonstrate to our students, again and again, that the photographers who achieve more vivid and dynamic images do so NOT because they rely on a limited set of camera features that have been designed by a team of engineers in order to address the properties of their scenes FOR THEM, they do so because they’ve been taught, more directly, how to understand and value the very underlying properties that those engineers were trying to address.

And whereas the engineers who designed our cameras were hamstrung by the limitations of their own generic system - a system that has to predict, in advance, how the lowest common denominator might want to take a picture, and then impose those assumptions onto the shooter….on the opposite end of the spectrum, photographers who practice the medium more directly, from OUTSIDE the rules of that limited and compromised system, are privy to hundreds of alternative ways for structuring an image, ways that aren’t always available to photographers who restrict themselves to the confines of such systems.

And if ASOP can teach total beginners how to perform to those standards in under a year’s time, then our culture should damn well expect professional photographers, who‘ve devoted their lives and careers to practicing this medium, to meet and exceed those same standards as well.

So the purpose of this article is to unpack this whole crazy mess - to explore and diagnose the various causes of how the industry got to where it is today, and then to offer a prescription for how photographers might be able to limit the influence that companies like Canon, Nikon, and Adobe have over our photographic standards and methods.

Final Introductory Thought:

What’s at stake here, or why does any of this matter?

Before we dive in, I’d like to offer one final note that goes beyond the scope of the current photography industry, and speaks more toward the far-reaching societal implications of what’s being discussed in this essay.

The endgame photographers need to be striving for here is a loosening of the powerful grip these companies have over the way that photography is practiced. And among the long list of reasons this needs to be done, the one that probably tops the list is the fact that the medium of photography represents a new and spectacularly useful form of emerging literacy.

This medium holds the potential to be a system of visual grammar that can completely alter human thinking, in much the same way that our written language helped advance human thinking in previous centuries. But the difference here is that, while our spoken and written languages were allowed to develop outside the influences of corporate profit models, photography is currently developing entirely within them.

In other words, while our culture is increasingly moving toward using word processors and apps that will auto-complete our sentences, and auto-correct our grammar (which will undoubtedly begin to affect the way we all speak and write), at least our written language was allowed to develop a great deal first, for several millennia in fact, before we then started imposing these kinds of paternalistic patterns and formulas. And at the individual level, the average person has been widely exposed to the written language (if not made totally fluent) before they’ve been offered such devices.

Photography, on the other hand, is a language that is having these patterns imposed upon it from the get go, before mass literacy has been achieved, and before photography has had a chance to develop into a more sophisticated mode of communication. And at the individual level, photographers are being offered these devices before they have any real understanding of the medium at all, which makes them entirely dependent on the companies who design them.

Thus, shifting control over the evolution of this medium back toward photographers themselves (and away from these companies) is likelier to result in a more sophisticated photographic language, and a world in which more complex images become the norm across all uses of photography, simply because it would encourage millions of photographers from across the globe to prod and explore until they’ve uncovered increasingly more sophisticated results.

In other words, it would allow for a more organic, more complex evolution of photography to unfold….as opposed to what we have now, which is a world in which these companies are boxing photographers in from the very start with a lot of pre-packaged solutions, and limiting them to a painfully finite set of pre-determined results.

And importantly, such a shift would also allow for photography to become practiced as a more conscious and more purposeful medium. Because at the moment, this is a medium being practiced in a lot of indirect and unconscious ways (and frankly, through a lot of trial and error), and also through a total dependency on the opaque functions designed by profit-seeking companies.

So in summary: photographers are increasingly becoming walled in, cut off from any true understanding of the medium they’re practicing, and are only able to engage this medium through a series of pre-determined, task-specific camera functions that were designed more to maximize Canon/Sony/Nikon’s profit margins than they were designed to expand our use and understanding of this medium.

And while that mode of photography may be convenient and useful to the more casual consumer, when that kind of superficial methodology is adopted by the very top of the industry, it puts an abrupt stop on the growth and expansion of this medium’s capabilities, as well as on the growth and expansion of our collective photographic language.

So let’s dive in, shall we?

Part 1: They Make Our Tools

How did we get here?

Well to begin, it needs to be established that just about any practice of photography is almost entirely dependent upon mass production.

While other kinds of artists have the option of relying upon mass-produced goods, they also have the option of developing their respective crafts with some modicum of independence. Painters, for instance, can create their own colors, or construct their own brushes out of new materials, they can also paint on surfaces other than stretched canvas. Sculptors can harvest their own clay, and fashion their own unique tools. Collage artists can make their own paper, and dye it with their own pigments, etc.

But when discussing the medium of photography, it is wholly unrealistic to expect photographers to form their own optical glass in order to craft their own lenses, or to build their own precision shutter, one that’s accurate to within 1/1000 of a second.

And even if they could, doing so would only cover the barest fundamentals of the medium.

If a photographer really wanted to practice this medium with any kind of efficiency, convenience, or adaptability, they’d have to engineer several different kinds of lenses, build their own flash units, and design a unique, customized operating system that might be able to coordinate all those functions together.

And even in the event that one single photographer had all of the knowledge and skills required for each of those tasks, they'd still need a team of dozens of specialized workers to help them, and the costs would be astronomical.

In fact, just to commission an existing company to build a custom system of lenses, sensors, flashes, and software (basically an entire "prototype" system) would likely cost hundreds of thousands of dollars on the low end, and millions of dollars on the high end, which means that, when it comes to photographic tools, total autonomy is not a realistic pursuit.

So we’re all dependent upon mass production in order to practice this medium at all.

One easy way to describe the current situation is that if it would be prohibitively expensive to build an entire custom photographic system, then what we've done instead is we've all collectively gone in together on a mass “group discount.” Companies build thousands of generic cameras/lenses/flashes for us, and that means we can all purchase a relatively complete photographic system for something more in the ballpark of $3,000.

Whereas, if cameras were made as boutique items, exclusively for the expert professional (the way that medical tools are made in small batches, exclusively for licensed surgeons), photographic systems would probably cost over $30k-$50k.

But unlike medical experts, our use of this medium is heavily subsidized by millions of casual consumers, typical citizens who buy cameras to use for recreational purposes, or to capture their special occasions and travels. And these millions of casual consumers increase camera sales immensely, allowing Canon/Nikon/Sony to offer their systems at a much lower price point. And that means expert photographers get to purchase their gear in the much cheaper "consumer" marketplace, as opposed to medical professionals, who are required to purchase their tools in the astronomically more expensive "industrial" marketplace.

But basically what this means is that we’ve gotten in bed with large, profit-driven, consumer-facing corporations not just for the supplemental aspects of our medium…but just to be able to practice this medium in any way at all.

Thus, the greater cost of going in for this ‘mass discount’ is that we've incentivized camera makers (who, remember, are the only plausible source for our tools) to develop their business models around their consumer clientele, who form a much, much larger portion of their market base, and are thus far more profitable to them.

And the expert photographer is then required to use a lot of equipment that has been manufactured to meet the demands and assumptions of millions of uneducated amateurs and hobbyists.

And this particular dynamic, wherein trained experts have to use equipment that’s been designed to satisfy the whims of a consumer-facing market is a relatively unique phenomenon for any professional field.

Doctors, for instance, rarely have their opinions brushed aside by medical supply companies who’ve suddenly pivoted toward selling their MRI machines and Lithotripters to a more profitable consumer crowd.

Or even just sticking within the realm of creative professionals, it’s unlikely that concert cellists have to worry that the designs of their cellos will succumb to corporate marketing gimmicks, or the misinformed whims of untrained consumers.

But photographers have to worry about that all the time.

So all of this is to say that if you want to engage in any kind of serious practice of photography, heavy amounts of compromise have been built into the process from the outset, from the very initial step in which you acquire the only tools available for you to practice this medium at all.

Which, again, seems a relatively unique dilemma.

Because while countless other modes of art and communication have been influenced by, and even compromised by consumer economics…very few have been forced to develop exclusively through them, the way that photography has.

Part 2: They Also Make Our Strategies

But here's the even bigger problem: it isn't merely the physical tools that are being mass produced; it's also the methodologies and the strategic approaches to the medium that are being manufactured as well.…ie: the actual paradigms about photography.

In other words, there are many biases and limitations being hard-wired into our tools, and then our subsequent methodologies and strategies are built around accommodating those biases and limitations.

And all of this heavily influences what people think photography IS, and how they think photography WORKS.

So what kinds of biases and limitations are we talking about, exactly?

Well, imagine that every photographic function on your camera - every shutter, every strobe, and most importantly, every algorithm - is essentially a solution to a photographic problem. And the way that each one came about is that, historically speaking, photographers were encountering logistical problems that prevented them from obtaining the exact results they wanted, so engineers began to design and patent solutions to those problems. And then, further down the line, large companies began to mass-produce those solutions.

And we’ve now arrived at a point in history where most photographers simply assume that those solutions were written in stone, from the very beginning of time, as the best, or only, way to practice this medium.

But the truth is, each of those problems had several, perhaps even dozens of potential solutions. It’s just that a lot of solutions won out simply because they were easier to integrate into existing equipment. Others came to market sooner and then came to be taken for granted by the industry. Some solutions were easier to explain to the consumer, and therefore easier to market. And some were simply more cost-effective.

The very boring and predictable bottom line on this is that the solutions that are more profitable, or easier to market to the public, are the solutions that tend to win out.

But that means that if certain solutions are being hard-wired into our equipment at the expense of others, it also means that certain BIASES are being hard-wired into our equipment, along with certain assumptions about how to even approach photography in the first place.

In other words:

The choices those engineers make often determine what kinds of approaches we can and can’t take in our shooting, which means the choices they make put very specific limitations on us…which, in turn, heavily influences our paradigms about how photography even works.

And this has always been true in at least some form.

As far back as 1900, the earliest mass-produced cameras forced photographers to conform to certain increments and measurements. For instance, early shutters were designed in “1 stop” increments, which basically meant that each turn of the dial would either double or halve the amount of light that was being exposed. And photographers had little choice but to accept those increments.

It was also manifest in the way Kodak's chemists favored certain film grains over others, which affected the overall look and texture of the picture, as well as the way a photographer might need to adapt their darkroom processes.

But this became infinitely and more poignantly true in the 1980's and 1990's by the way Canon and Nikon chose to design the operating systems and algorithms that govern the camera’s physical functions, ie: the algorithms that indicate which particular apertures and shutters you should use..…the algorithms that try to take the picture for you.

At that point it became not merely the physical components of photography that were being mass-produced, but the actual STRATEGIES of photography as well. For instance, the way your camera’s “metering mode” determines which part of the scene you should expose for, or how the Aperture Priority Mode determines the length of your exposure.

Further, the engineers who were designing cameras way back in 1900 were making decisions for a relatively small and knowledgeable community of photographers, which meant that when it came time to make decisions that might restrict what a photographer could do, they had to use the best of their abilities to determine what might be the “lesser of all evils,” knowing full well that their customers might be aware of what compromises have been made.

Thus, they made a lot of those early compromises and restrictions “in good faith,” and probably somewhat apologetically.

But today the most restrictive decisions made by Canon/Sony/Nikon are made far more intentionally, and they’re aimed at a much less knowledgeable group of consumers. And when those decisions are made, they aren’t at all seeking the “lesser of evils;” they’re very clearly making decisions that prioritize profitability over the most expansive or logical needs of expert photographers.

Or worse, they’re making decisions based on the desire to manipulate the assumptions and perceptions of an unknowing consumer public.

Alright, before all of this gets to be a bit too dense, I‘d like to pause for a minute here and more concisely summarize the dilemma that’s being established in this section:

For any photographer out there with ambitions to mastering this medium, you first need to be aware that our tools, as well as most of the strategies that accompany those tools, have been designed to manipulate the whims of a CONSUMER marketplace, a marketplace whose participants understand very little of how photography works beneath the surface of the interface they’ve been given by these camera companies.

And this has given these companies a lot of unquestioned, unilateral control over how this medium is understood and practiced.

Thus, instead of a power dynamic in which these manufacturers respond to the needs of experts and industry leaders, we have the opposite. We have a power dynamic in which these manufacturers set the paradigms and standards for photography however they want…… because they’re doing so for a largely photo-illiterate consumer public. And therefore they do it in ways that more reliably benefit their own preferred business models, as opposed to in ways that more universally improve and develop this medium.

In short: this has left us with an entire industry where, instead of camera makers responding to the demands of knowledgeable experts, it’s evolved to be exactly the other way around: professionals photographers are learning all of their “expertise” from Canon/Sony/Nikon product reps.

Or one last way to describe the situation would be to say that the basic economics of the camera industry work something like this: Camera companies create the “supply” of products that they prefer to make first, and then after they’ve determined which products will be the most profitable to themselves in the long run, they then work really hard to generate “demand” for those products among photo-illiterate consumers, through a sophisticated system of marketing strategies.

And then photographic experts are stuck working with whatever tools emerge from that process.

And this has been the origin story for nearly every piece of camera technology that’s hit the market in the past half-century.

And just to keep in mind what’s at stake here: these companies are essentially the gatekeepers to the only realistic tools we have in order to access and develop what might be the most important and influential form of human language to emerge since the written word.

…which means this is a massive, massive problem.

Part 3: Professional Photographers Are Largely Unaware of This Dilemma

Ok, so here’s maybe the very deepest part of the problem: we’ve now arrived at a point where most photographers (particularly most professionals) now just assume that the solutions that Canon and Nikon have chosen are simply, inherently, "how photography works."

People now look upon their camera's engineered functions (not just the physical functions, such as the shutters and the apertures, but also the strategic functions, such as the metering modes, the histograms, and the auto-bracketing) and they take for granted that those functions ARE photography, which is to say that when people are learning about metering modes, histograms, and auto-bracketing, they think they're learning "photography.”

But those functions aren’t photography.

Photography is the underlying phenomena those functions were designed to address. For instance, the need to record one amount of light in your scene as opposed to another. Or the need to emphasize one layer of space in your scene as opposed to another. Or the need to allow one amount of time to pass while the picture is being recorded as opposed to another. Etc.

Those are the inherent properties of photography. And each of those properties can be addressed in dozens of potential ways.

Histograms, metering modes, exposure compensation dials, etc., are not inherent properties of the medium. Each of those functions is a limited solution that some engineers developed in order to address these properties in a relatively generic and affordable framework ….solutions that could then be standardized and mass produced, and - most importantly - monetized.

Thus, if one’s act of "learning photography" consists mostly of studying metering modes/histograms/camera features, etc., it needs to be made clear that you aren't really learning Photography, you're learning one very limited and biased translation of photography.

So in light of all this, consider that we can now break the world into two classifications of photographers:

1) Photographers who deeply understand the medium and its properties INDEPENDENT of the equipment they’ve been given… who then build and adapt their strategies as cleverly as they can around the mass-produced equipment they have no choice but to use.

2) Photographers who don't really see or understand this distinction at all, who instead have learned photography exclusively THROUGH their camera functions and their “tech,” and who believe that the framework that Nikon/Sony/Canon have hardwired into their cameras IS photography.

And at the time of this writing, most photographers, including the overwhelming majority of professionals, tend to be the latter.

And to understand why this dynamic has become so counterproductive to the development of this industry, let’s first examine the distinctions in how these two types of photographers behave and operate, and then we can examine the kinds of images that result from either behavior.

Part 4: Two Very Different Approaches To This Medium

The first type of photographer (we’ll call them "Type A") understands the properties of a given scene very directly, independent of their unique camera interface. They understand all of the ways that light, distances, spatial relationships, angles of movement, etc., can affect their images, and they know how all of those assets can be addressed and exploited directly.

And for the record, as daunting as all of that may sound, these skills aren’t particularly difficult to acquire. In fact, I’ve spent the past decade proving that just about anyone can learn to do this. The difficulty of practicing “direct” photography is about on par with the difficulty of operating a motor vehicle, which is to say that it may appear very alien and complicated to someone who’s never done it before, but it takes only a few months for the average person to learn how to do it both comfortably and competently, and it certainly doesn’t take a science wiz to master.

But if we were to elaborate on just one of those photographic dynamics I just mentioned, let’s say, the LIGHT within the scene, our Type A photographer knows how many ways that light can be useful, how many ways it can be captured, how many ways it can be used to change the emphasis of the image, or change the shape of the image, how many ways it can conceal or reveal parts of the image, and finally, how many ways it can be used to alter the sensibility or the mood of the image.

At which point this photographer willfully and “directly” chooses the exact manner in which they prefer to exploit that light.

In order to do so, this photographer uses mostly manual functions, which are still somewhat limited by the choices that the engineers made in building them, but at least in using fully manual functions, this photographer has taken the programmed responses out of the process.

In other words, while this photographer has no input into how the physical aspects of the camera have been designed (the apertures, shutters, and focal lengths), they do have full autonomy over how those mechanical functions are to be deployed, which means this photographer has taken the pre-imposed strategies out of the process.

In short, this photographer no longer has to worry that the camera’s predetermined responses will interfere with what they are doing, which means they don’t constantly have to “fight” with their camera.

And that ensures that this method is faster and more efficient (which surprises most people, but is actually very easy to demonstrate). It also ensures they can achieve a greater variety and complexity of results, and also achieve more exact results, which means far less time is wasted using post-processing software.

But importantly, this method requires real knowledge of the medium itself, and not just knowledge of the camera's operating system, or the proprietary solutions designed by Sony or Adobe.

The second type of photographer (“Type B") practices photography very differently.

Type B photographers forego learning the underlying, universal properties of photography, and instead choose to learn (and to trust) Canon’s or Sony’s proprietary technology. In other words, they learn Canon/Sony/Nikon’s operating system - all of the most “advanced” and “professional” features of their cameras - and then they learn Adobe’s post-processing solutions.

But the problem with this approach is that a camera’s operating system isn’t a neutral reflection of how photography works. A camera’s operating system is a reflection of the decisions and preferences of the engineers who designed it. It’s a very limited system of programmed responses (a set of pre-packaged solutions, and - more importantly - a set of rules and restrictions), written by people who are total strangers to you, in order to capture your images in one way as opposed to another.

In short: your “tech” is merely Sony/Canon/Nikon’s singular, proprietary translation of photography.

It isn’t photography.

And going all-in on this translation is problematic for two very big reasons.

The first reason is that it is cumbersome and inefficient. In being somewhat abstract and indirect, this approach often overcomplicates things that don’t need to be complicated at all, which in turn leads to comical amounts of unnecessary logistical steps, as well a lot of unnecessary compromises.

For a quick glimpse into what I mean by that, as an analogy, imagine if our next generation of automobiles were designed so that, in order to change lanes, rather than just gently turn your steeling wheel for a moment, you instead had to hunt through a chaotic system of “change lanes functions” in your car’s operating system……and from that analogy you’d get a pretty good idea of how modern cameras are overcomplicating photography.

The second reason this approach is so problematic is that the choices the engineers have made tend to paint you into a corner, limiting the complexity and variety of results you can achieve. And that, in turn, affects your overall strategies and shot selections in ways that sometimes force photographers to settle for a lot of simplistic and mediocre images.

And this means these two types of photographers don’t just operate differently, they also end up with entirely different kinds of images.

So let’s go ahead and more thoroughly unpack each of these two problems with the “Type B” approach, beginning with that first concern: the messy INEFFICIENCY of an algorithms-based approach.

Once you start down the path of using your camera’s algorithmic features (even the more “professional” ones), the problem you quickly encounter is that the engineers at Canon/Sony/Nikon can’t predict exactly what you want to do from one scene to the next. So when they’re writing their algorithms they make a lot of generic, lowest common-denominator assumptions about what the common consumer PROBABLY wants (recall that their largest customer base is consumers, not professionals).

For instance, statistically speaking, most amateur photographers place their subject in the center of the frame. They also tend to compose the subject so that it is nearer to the camera than other parts of the scene. Etc.

In other words, these are the kinds of choices a layperson makes when they’re shooting friends and loved ones at birthdays and weddings.

And the reason most amateurs do those things, by the way, is because they aren’t really interested in creating a more complex message, or even a more complex relationship between two different parts of their scenes.

They’re mostly just trying to record, or “show,” us something.

So the engineers at Canon/Sony/Nikon tend to program the camera’s responses with a lot of those basic assumptions in mind. For instance, they might program the camera to prioritize exposing for whatever’s in the middle of the shot, or to focus the lens on the part of the scene that’s nearest.

But again, that system has initially been designed for amateurs, who purchase the vast majority of the cameras these companies produce.

If on the other hand you’re a pro photographer, or if you’re simply a ‘more serious photographer,’ one whose shooting might stray from those expectations, then those core program functions will not be sufficient.

So to satisfy those photographers, the engineers tack on even more algorithms — more indirect technical abstractions — that are meant to “correct” the camera’s behavior in very specific circumstances.

Think of it like this:

All cameras are initially programmed with the most basic layperson thinking hardwired into them. And then, for “Type B” professional photographers the idea of “controlling your image YOURSELF” is not to bypass this paternalistic programming altogether — shooting manually and more directly — nope, their idea of “controlling the image yourself” is to ACCEPT this base-level programing, but then to use some extra functions that might override it.

And those “extra functions” I’m referring to are the so-called "advanced features" of a modern camera — features such as exposure compensation, exposure lock, metering modes, histograms, auto-bracketing, etc.

These are the kinds of camera features that most professional tutorials are built around.

So rather than starting from scratch, with pure, universal photographic knowledge, these photographers are starting from a biased and fallible platform….and then they learn how to AMEND that platform.

And the photographers who use this approach often have to fumble through a half-dozen clumsy steps to override the assumptions made by the engineers, only to still miss a lot of shots and still end up with imperfect results.

At which point they spend several hours using post-processing software to “fix” and finalize those results. Which is where companies like Adobe step in, all too happy to introduce even more proprietary algorithms into this Photography Industrial Complex.

Or to put all of this much more concisely:

And this is how Type B photographers honestly think photography works.

Rather than learn to shoot “directly,” they’ve been taught to anticipate the mistakes their camera’s programming will make, and then they learn what functions they can use to override those mistakes.

And so what’s the overarching consequence of this kind of thinking?

Well we’ve now arrived at a point where most pro photographers whole-heartedly believe that “true expertise” means using multiple override functions until you get sort of an APPROXIMATION of the image you want (often in a trial-and-error like fashion), and then you spend several hours using post-processing software in order to fix the image, after-the-fact.

Trial-and-error…and then several hours in post.

That’s what it’s come to.

And while many of these photographers won’t quite see it this way, because their process has become so obscured (and “legitimatized”) by a fog of esoteric functions and jargon…that’s essentially what they’re doing.

So wait a minute. Professionals are really just using a lot of trial and error?

Yes. And in almost everything they do. In fact, infuriatingly so.

Later in this piece, I’ll get to the very bottom of exactly how I think we got to this point, but maybe the first thing that has to be understood here is that this kind of methodology is widely reinforced — at every opportunity — by the manufacturers who sit at the very top of the industry. Because, in addition to designing our interfaces in ways that often emphasize, or even promote, these kinds of override functions, many of the tutorials these companies publish, on their own social media pages, very openly advocate for using these functions by way of trial-and-error.

For instance, if you watch a lot of the video tutorials put out by companies like Canon, Sony, or even Profoto, what’s very typical is that the photographer hosting the tutorial will begin by snapping an image, and then examining the image’s ‘histogram’ to discuss what adjustments they think need to be made…

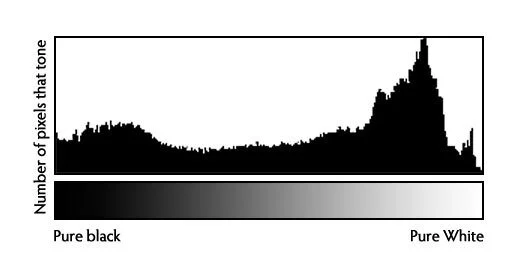

[Quick Aside: For those who aren’t familiar with the term “histogram,” it’s basically just a graph of all the pixel information in a given image, which pro photographers like to use in order to see if they “got their exposure right.”

It looks something like this:

The basic gist of the histogram is that, instead of being a tool that enables you to measure and evaluate the light in your scene BEFORE you begin shooting - so that you can get your desired result on the very first try - the histogram is the opposite, it’s a tool that encourages you to take a more “blind” image first (which basically means letting one of the camera’s algorithms take the picture for you), and then you can check your pixel data AFTER-THE-FACT, so that you can try again with a different “override function” if you don’t like the results]

…..so the host of the tutorial will begin by snapping an image, and then looking at the histogram of the image they’ve just shot. And then they’ll explain to the viewing audience how they think they should adjust their camera for the next take (ie: which “override” function they should use)…and then they’ll snap another image…..and then they’ll look at the histogram again..…and so on.

And once you get past the abstraction of the histogram, this methodology is just a glorified version of trial-and-error.

And perhaps the strangest dynamic in all of this is that I’m fairly certain the photographers who are hosting these tutorials, themselves, aren’t particularly aware that they’re just using trial and error, because, to them, the notion of employing some kind of esoteric “correction” tool on their camera in order to move their “histogram” just sounds super legit.

But I think what that tells us is that normalizing these kinds of proprietary abstractions, and then standardizing them into our camera’s operating systems, works really well to disguise the fact that there’s nothing particularly substantial about this process at all.

Because while these abstractions may sound very technically complex to the newcomer, in actuality, using these kinds of solutions really just limits and narrows the way a photographer understands and practices this medium, all without providing them any real insight or understanding about what’s happening beneath the surface of those abstractions.

Which means, in effect, these abstractions simultaneously limit the photographer while also keeping them dependent on opaque, proprietary technology. Which is decidedly problematic for the development of an individual photographer.

But then on top of that, these technologies also give the professional photography community (as a whole) permission to keep shooting blindly until they finally get a good result. Because when it’s done in this manner — through all of these obscure functions and jargon — suddenly it’s no longer “just shooting blindly, via trial and error”…..it’s now perceived as a “legitimate technical process.”

So in summary:

These functions both disguise and legitimize the fact that these photographers are really just using trial-and-error. And perhaps more importantly, they give photographers the impression they’re using legitimate expertise, when in reality they’re just being boxed into a very limited framework.

And then viewers of these tutorials watch as a bonafide professional photographer - in fact, an ambassador for an internationally elite photography company - stumbles through the process of getting a satisfactory image capture over the course of a 30 minute video, which then greatly reinforces the idea that “this is just how things are done.”

But this kind of advice isn’t limited to the promotional tutorials put out by Canon and Profoto. It can be found pretty uniformly across the widely popular tutorials published on the blogs and Youtube channels of acclaimed professional photographers..….and on larger aggregate sites such as Fstoppers or Petapixel.

In fact, it’s on these kinds of forums where you’re most likely to encounter tutorials — professional tutorials, mind you, such as how to take bridal portraits, or how to shoot architectural interiors — in which honest-to-god industry pros advise their readers to just “fiddle around with their settings until the picture looks right.”

So before moving on, I’d like to add one final layer to all of this.

The only way it can possibly make sense to a photographer that “fiddling around with your settings” could ever be the best approach is if that photographer intends to make only the most simplistic or formulaic images.

Because.…….yes…….if you’re taking very simplistic, very formulaic images, then it can certainly be imagined that a few minutes of “trial and error” is a more practical solution than, say, spending several months studying and mastering every last nuance about the science of photography.

But any photographer with a more direct knowledge of the underlying components of the process will understand that not only can these techniques be handled more quickly when you shoot manually (way, way more quickly), but just as importantly, shooting more directly allows you to combine several photographic components and decisions in ways that could never reasonably be accomplished through “trial-and-erroring” your camera’s built-in solutions.

Which means these technologies not only slow photographers down, but they also place a very defined limitation on the overall complexity of their images.

So one important thing to keep in mind here is that this “industry standard” of taking very simplistic, very formulaic images is a seed that has largely been planted by the camera companies themselves.

In other words, these companies have set a standard for how professional images are “supposed to look,” based on what their own technologies are good at.

And then once that standard has been widely established — and once those images have become the norm throughout the industry — they can then advertise their own technologies as the very best path toward achieving those goals and standards.

Which means they’ve essentially loaded the question of “how photography works” so that they can provide their own preferred answer to that question. And their final sales pitch can perhaps best be summarized as follows:

“Look, there’s really no need to learn ‘photography’ — just learn our technology instead…..because our technologies can handle the very limited set of images that WE’VE established as being the “industry standard.” And then when those technologies fail - which will happen a lot - we’ll show you how to smooth over the edges with a bit of trial and error.”

And I can never decide which part of this is more appalling: that the camera industry continues to push these paradigms about photography….or that professional photographers continue to eat it up, seemingly without any awareness at all.

Either way, when you now hear professional photographers scoffing at the idea of, for instance, having to use an actual light meter in order to measure the light in their scenes (and almost all of them will scoff at that idea), ironically, those photographers think they’re signaling their own expertise, by insinuating: “Eh, if you really know what you’re doing you don’t actually need a light meter, you can just wing it.”

When in actuality, they’re signaling their lack of expertise by demonstrating how much they’ve bought into Canon/Sony/Nikon’s paradigm of taking extremely simplistic, formulaic images. They’re signaling that they’re wholly unaware that this medium can be used to create more sophisticated images than the repetitive formulas they’ve learned to mimic.

And so, yes, using trial and error makes perfect sense to them. Because when you get used to shooting the exact same kinds of simplistic images over and over and over again, then “just fiddling around with your settings for a minute” is indeed a viable approach.

But finally, getting back to these popular online tutorials, the real coup de grâce is always the part that comes next.

After watching a photographer spend upwards of 30 minutes stumbling their way toward a finished image, if the tutorial or video has been published on social media, it’ll almost certainly be accompanied by a cacophony of enthusiastic comments from other photographers exclaiming “Great tutorial! I learned so much!” …a statement which almost can’t possibly be true.

But due to the highly opaque and abstract nature of these technologies, it has become very difficult for aspiring photographers to know what’s real and what’s snake oil.

And the end-result here is that professional photographers routinely spend several minutes (and often 10-15 takes) trial-and-erroring their way to an image that a more knowledgeable photographer can achieve instantly, in just one try.

So in summary, the first real problem with the “Type B” approach is that it carries with it an almost comical level of inefficiency, as well as a frightening amount of trial and error.

Rather than be trained to understand the actual, inherent properties of photography that dwell beneath the surface of their technology, “Type B” photographers have instead been trained to recognize patterns and reference points on their camera’s interface — patterns and reference points that have been engineered FOR them, and then marketed TO them.

And that has made the process of photography unnecessarily indirect and abstract for them (and also painfully time-consuming).

But as mentioned before, the second and more important concern here is that this approach also leads to a lot of generic and simplistic images.

Why?

Well, to understand this part, we have to get back to that idea of “photographic variables.”

Algorithms hate variables. Because variables interfere with an engineer’s nicely laid plans.

For instance, if there’s a big difference in light within your scene (ie: if a scene has a lot of bright highlights AND dark shadows), then the algorithms that control your exposure are likely to become confused, as they won’t know which part of the scene to expose for, and you’ll begin chasing a chain reaction of corrective functions on your camera to get the exposure you want.

Or if there are wildly different layers of space within your shot (ie: one thing is very near AND another thing is very far), the algorithms that deal with focus and depth of field will get confused, and you’ll begin chasing a chain reaction of corrective functions on your camera to get what you want.

And so, due to the fact that these algorithms are so easily confused by these kinds of variations, when it comes to STRATEGIZING an image, most photographers have actually been taught to avoid these variables altogether, because doing so greatly cuts down on the amount of misfires, and the amount of trial-and-error, that they’d have to endure.

In other words, whereas someone who shoots manually, and more directly, can handle these kinds of variations very easily (recall my “changing lanes” analogy from earlier), on the opposite end of the spectrum, if you’re trapped within a limited system, one that was programmed via the assumptions of an engineer who isn’t even present at the time the picture is being made, then the only solution is to try to override the camera’s programming.

And then the insurmountable problem becomes that, due to how cumbersome and time-consuming each one of those override functions is going to be (and also how much trial and error they often require), at best, you’re only going to have time to overcome maybe one variable within your scene…if that.

And so these photographers have been taught to avoid those variables, to avoid that kind of complexity. They’ve been taught that if there are wildly different amounts of light, or wildly different layers of space, or a lot of movement throughout the scene, the camera's algorithms will continue to give them unpredictable and inconsistent results, and they’ll miss a lot of shots trying to correct for it.

Thus, much of what passes for conventional wisdom - in workshops and tutorials - stems from the need to eliminate these “inconvenient” variables.

For instance, photographers like to repeat the advice that it’s best to shoot during the ‘golden hour,’ as opposed to at high noon. Or that, if you’re a portrait photographer, you should bring your subject into a shaded area to ensure very even lighting.

These have become almost unquestioned bits of “common wisdom,” or “rules-of-thumb,” within the industry.

And if you read between the lines, what this advice is really saying is “Avoid high contrast situations, because you’ll have to spend a lot of time and effort ‘correcting’ the camera.”

So whereas the more knowledgeable, more direct photographer understands that lighting differentials are what allow you to shift the emphasis of a photograph, or sculpt the shape of a photograph, or alter the mood of a photograph (which will all be demonstrated later in this piece)…these “Type B” photographers are actually being taught to avoid lighting differentials at all costs.

Perhaps the more biting way to put it is that, “the engineers who designed your camera politely ask that you not put anything in front of your lens that will foil their nicely laid plans to take your picture for you.”

So at the end of the day, if we put all of this together, “Type B” photographers are learning their methodology in two big steps:

Step 1: they spend several months learning their “tech,” getting to know their operating systems, and all of the various shooting modes and ‘advanced features’ on their cameras….and then,

Step 2: because those functions are so easily confused by any variables within the scene, they learn to avoid those variables almost entirely. Rather than elevate their abilities to meet the complexities of the scene, they learn to “dumb the scene down” to match the capabilities of their algorithms.

Or perhaps the even better way to put is that they first learn all of the functions that allow them to fight with their cameras, and then they learn that if they choose a simple enough scene, they won’t have to fight so much.

And as already noted, most of these photographers don’t know that this is what they’ve been taught, because these methods (and these technologies) have been wrapped so tightly in a veneer of technical jargon that “Type B” photographers truly believe they’re learning something sophisticated.

Part 5: The Images They Shoot

The upshot of all this is that “Type B” photographers stick to generic, fail-safe formulas that are explicitly designed to ensure that their camera’s programming will never get confused.

In other words, if you look at a lot of the more repetitive and formulated professional work that’s out there you can see this mindset on display. Because once professional photographers have bought into this algorithms-based approach, they’re all sort of stuck shooting the same images as everyone else. In fact, many of these photographers have near-identical portfolios.

For instance, every family photographer has the shot of the family sitting in a field of bluebonnets. Every food photographer has the overhead shot of the plate. Every senior portrait photographer has the shot of a teen in front of a brick wall. Etc.

And in looking at those images, consider that there’s a very logical reason these shots came to prominence. The lack of variables ensures that these are all formulas that allow professional photographers to bypass having to really understand the properties of the medium at all, because these are images that the generic algorithms of their cameras CAN handle, which in turn, allows them to learn their camera technology instead of learning the underlying properties of photography.

And one of the more prevalent consequences of all of this is that if all pro photographers shoot the same pictures, it forces them to compete with each other using primarily non-photographic skills.

So portrait photographers become adept at location-scouting, learning how to find the best gazebo, the best field of flowers, or the best railroad tracks. Wedding photographers develop their customer relations skills, becoming more adept at dealing with highly-stressed couples. Photographers of all varieties take classes on SEO optimization and online marketing.

Etc. Etc.

Because if “Type B” photographers can’t distinguish themselves through their shooting — and all of them have identical portfolios — then these more peripheral factors are likely to determine their success in the market. And so most professional photographers have been instructed to concentrate on these skills instead….almost exclusively…to the point that these more “supplemental” skills now monopolize the entirety of their education.

Which is why I now routinely meet pro photographers who’ve attended multiple workshops on portrait posing, or website management, and who can immediately regurgitate all of the talking points they picked up in each, but who don’t seem to understand even the most fundamental principles of how light works, or how lenses can be used to manage the spatial relationships in their scenes.

But returning to the shooting itself, in order to illustrate the different results that each of these approaches leads to, let’s more closely examine some apples-to-apples comparisons between pro photographers shooting the same kind of subject matter, but while using vastly different methodology.

And I’d like to begin by returning to that wedding comparison that initially kicked off this discussion.

I can now more clearly state that this first batch of images was shot with the ‘Type B’ methodology we’ve just outlined. And upon second viewing, it should be a lot more obvious now how these photographers have been taught.

Specifically, they’ve been taught a formula, one that was designed to avoid all major photographic variables, so that they can continue to use the smart-sounding camera features they learned about in their workshops:

…so they stage their scenes to be as flat, static, and evenly lit as possible.

And then, because that process can result in some fairly dry and simplistic images, many photographers will resort to spicing up the final outcome in ‘post,’ perhaps by adding some artificial color saturation (as has been done to the image in the lower right), or by using a pre-packaged filter effect, such as an artificial glow, or a vignette…not unlike the pre-packaged “filter” options you’ve probably seen in your Instagram app.

But it needs to be noted that post-processing software can’t really be used to re-structure the image - physically speaking. It can only be used to add an artificial veneer on top of the image you’ve already structured.

And moreover, artificially “spicing” an image can frequently cause it to look a bit cartoonish (again, note the image on the lower right). This is because if the proper photographic dynamics and variables truly did exist in the original scene, then those dynamics can easily be enhanced with post-processing…..but if they were never there to begin with, then adding them artificially can often defy our senses and expectations in some pretty unsettling and even silly ways.

For comparison, let’s now take a look at some Type A wedding photographers who instead look for scenes (or even create scenes) that legitimately have different amounts of light, disparate layers of space, and movement variables, in order that they may punctuate their images with a lot of emphasis and sentiment:

These photographers aren’t afraid of photographic variables; they‘re seeking them out and exploiting them. They see each variable as an opportunity to alter the structure of the image, which means each is an opportunity to “voice” the image with a more particular sentiment or energy.

Moreover, because these dynamics actually existed in the scene itself, if these photographers want to ENHANCE those dynamics with post-processing software, they certainly can.

However, let it be noted that: 1) It often isn’t necessary; in fact a good percentage of the student images in our ASOP Gallery haven’t been subjected to any post-processing at all, and 2) had these dynamics NOT existed in the scene, a lot of them would have been very difficult, or at least irrationally time-consuming, to fabricate using processing software.

The bottom line on post-processing is that creating the image in-camera, while the actual scene is still in front of you and at your disposal (as opposed to doing it with processing software, after-the-fact) is almost always faster and more efficient, and without exception ALWAYS provides you with more possibilities for how you can structure your shot.

But that’s the exact opposite of what pros are being taught.

They’re being taught to make quick, “generic” images in-camera, and then to do the “real work” later on using processing software.

And the incredibly specious logic they like to regurgitate in order to justify that approach is that, if you keep your “image capture” as generic as possible, then you can better enhance the image later on, maybe even take the image in 4 or 5 different final directions… whereas if you “commit” to a final result now, in-camera, you might not be able to “undo” it later.

Or to state their philosophy more concisely: “Surely 5 potential outcomes is greater than 1.”

And, I mean, who could argue with that, right?

So as a quick digression, let’s just stop and examine this premise for a minute. Because this particular premise - perhaps better than anything else - perfectly illustrates the kind of misunderstanding that inevitably arises when pro photographers learn a lot of “technology and jargon,” as opposed to learning photography.

What the pro photographers who espouse this philosophy clearly don’t understand is that the real-life physical variables that exist throughout your scene can be exploited and combined into hundreds of different image constructs, most of which will collapse entirely once you pull the trigger, and most of which then can’t be re-created in post-production.

So this means that at the actual moment of shooting — while still standing in the middle of your scene — there are literally hundreds of ways you can capture the image that might involve exploiting different variables in different combinations, and each one to different degrees. And the moment you pull the trigger, most of those possibilities vanish.

And while pro photographers (somewhat insanely) see this as an incentive to take the most generic picture possible, what they need to be taught to see instead is that if you want certain kinds of complex results, most of those results HAVE to be achieved in-camera, because they can’t be achieved through post-processing…..all of which more logically incentivizes you to put more substantial effort into your in-camera strategies.

Or to be a bit more specific, the way the physical process of photography works is this: depending on how many physical variables your scene has, you might have a matrix of 128, or even 256 structural possibilities. And nearly all of those constructs become unavailable to you once you pull the trigger on a totally generic image capture.

So given that knowledge, a more effective approach to the shooting process might look something like this: First, you survey your scene and recognize that there’s a very large set of possibilities for how you can structure/capture your shot. Next, you more selectively decide which possibility, or possibilities, you want, and which ones you don’t want. And then finally, even if you want to extract several different kinds of shots — or several different constructs — it takes only a few moments for a knowledgeable photographer to do so, in-camera.

Because it bears repeating that most of those constructs CAN’T be achieved by shooting a generic shot and then trying to re-work the image in post, which is to say, the most sophisticated structures quite factually have to be achieved in-camera.

So where “Type B” photographers have been taught to see their image capture strategy as “5 is greater than 1,” …..a more knowledgeable photographer will see it as “256 possibilities is greater than 5.”

Which is incredibly obvious to anyone who gives the matter even the slightest bit of thought.

But the fact that so many pro photographers (and seemingly all photography instructors) can’t see this logic indicates to me that they’ve never really questioned their training.

What most likely happened was this: when they were first learning their professional protocols via some kind of professional workshop, a very confident-sounding industry expert — ie: someone already well established within the industry — used a ton of esoteric and legitimate-sounding jargon to explain to them that if you defer all of your creative decision making to post, then you have 4 or 5 or 6 directions you can still take later on…….oh, and also, that’s what all “real pro photographers do.”

And upon hearing this argument, it all sounded logical enough.

And moreover, it was coming from the mouth of a confident authority figure (which is something those novice photographers were very much looking to become). So they didn’t feel the need to particularly question it at all. Instead they just immediately started regurgitating that same philosophy to anyone who would listen, so that they, too, could be perceived as an authority on the matter (“Bro, you should always center your histogram, you gotta capture as much pixel data as possible”).

But this notion that you should defer most of your creative decision-making to post-processing is an absolutely terrible paradigm, and it has probably done more to limit professional photographers than anything else we’re discussing on this page, as it means the vast, vast majority of image outcomes are entirely unavailable to any photographer who was simply taught, “make sure you always shoot in RAW so you can do tons and tons of post-processing later on.”

However it should probably be noted that this paradigm is profiting Adobe immensely.

Because while Adobe can claim no ownership over the ways the actual physical properties of your scene can be exploited and combined, they can claim ownership over the superficial “veneer” that their software allows you to overlay on top of your very generic image capture.

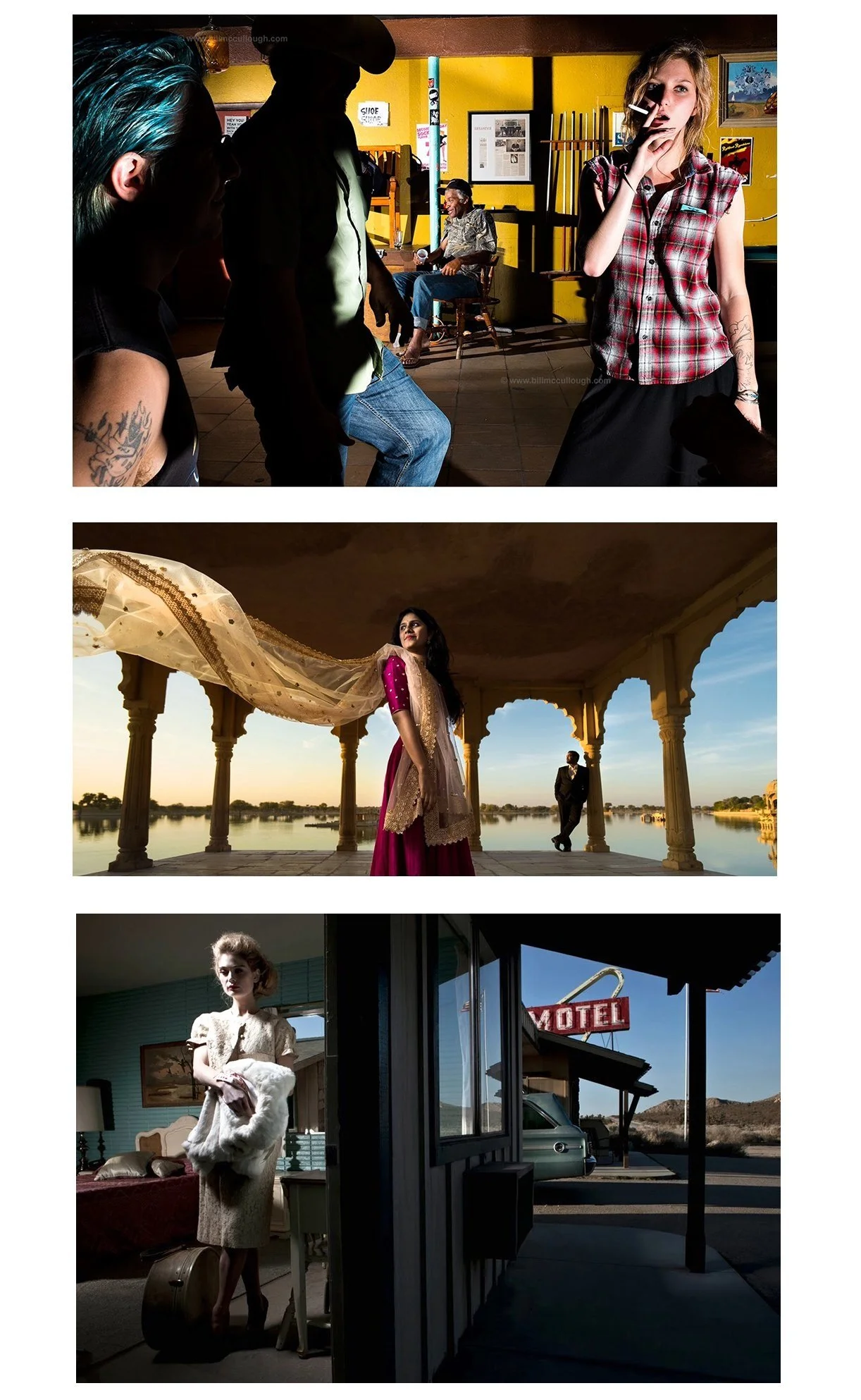

But back to our discussion. For our next comparison, let’s take a look at some Type B portrait photographers.

Once again, as with the last comparison, you’ll see that these pros are actively avoiding all photographic variables, which means their images are entirely reliant on only two factors: location and posing.

Further, note how even the location and posing have been neatly distilled into a series of repetitive formulas and clichés. So despite the staggering similarities you’re going to see in each row of images here, just know that every one of these images was shot by a different photographer:

So again, you can see that 100% of the work went into the location and posing. Which is to say all of the effort has been aimed at what to put IN FRONT OF the camera, and almost no effort has been aimed at what TO DO WITH the camera.

And this is because Type B photographers have spent their entire education concentrating almost exclusively on these more peripheral skills, and when it comes to the actual photography part of their job, in place of genuine photographic knowledge, they’ve really more just learned how to “manage” or “guide” their technology.

And in my experience, most of them don’t seem to know the difference.

From talking with them, it’s pretty clear that a lot of them even see the ‘photography’ part of the job as kind of a nuisance, something that just gets in the way of their posing and staging.

In other words, they see the photography part of the job as “a problem that needs to be managed,” rather than as an opportunity to do something creative.

So they learn to neutralize that part of the job as much as possible, by ridding their scenes of any photographic property that might obstruct their cameras, which in turn allows Canon/Sony/Nikon’s engineers to handle the actual photography part for them.

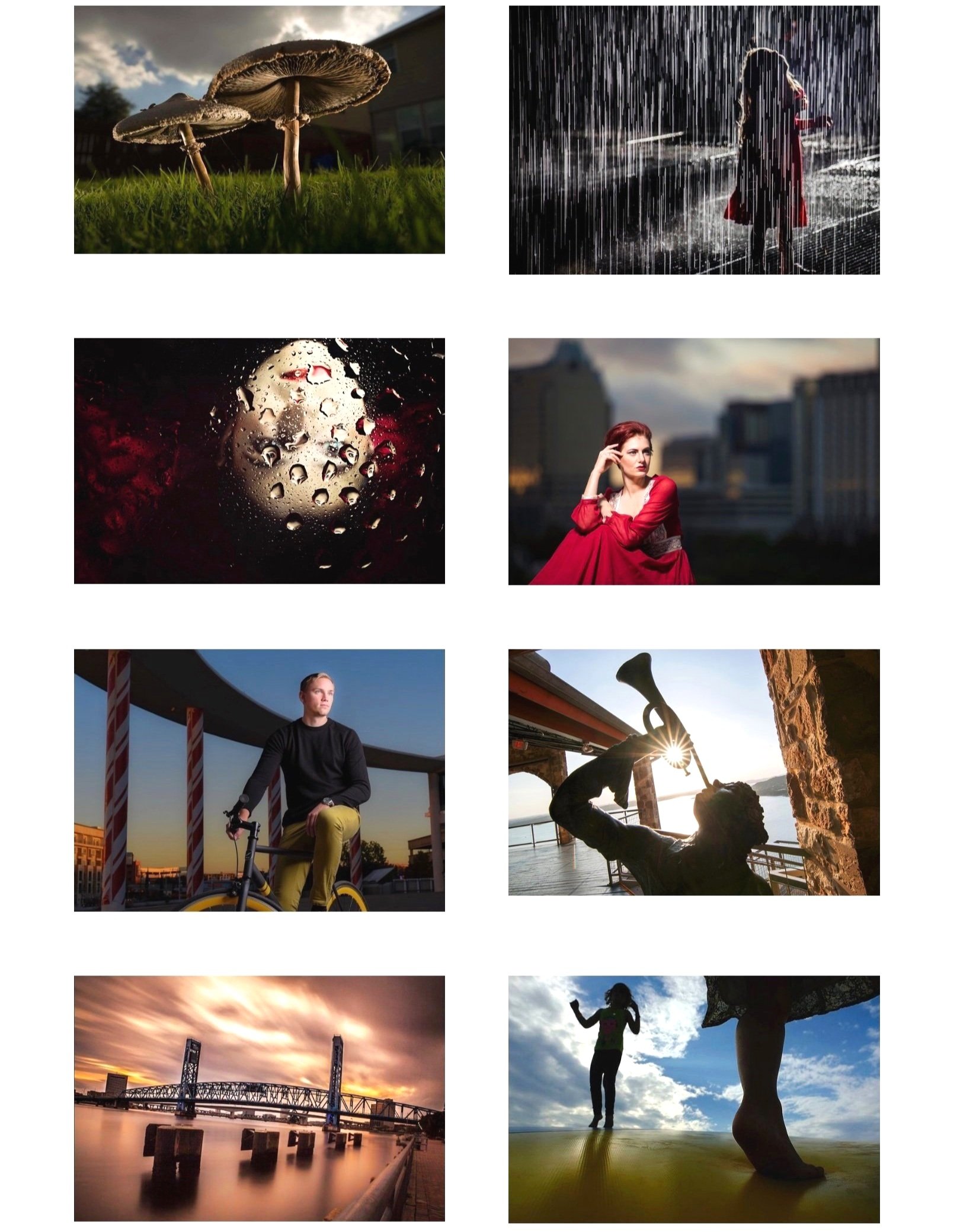

But now here are some portrait photographers who are embracing photographic variables. In fact, many of these photographers are even using studio lighting equipment in order to generate lighting differentials that were’t originally in the scene. This means not only are these photographers exploiting variables that were already present, but they’re also adding some additional variables that were’t:

So once again, the effects in these shots have been created through the exploitation of the very real variables these photographers have engineered into their scenes, which again, is much faster and more efficient than doing it in post-production (and many of these dynamics couldn’t really be faked with processing software anyway, particularly those involving spatial relationships).

Further, many of these photographers are still making use of the peripheral issues we discussed earlier (location and posing), it’s just that, on top of it, they’re also applying some photographic skills in order to express each subject with a distinct sensibility, style, or energy.

But just to speed things up a bit, let’s do a couple more quick, rapid-fire comparisons:

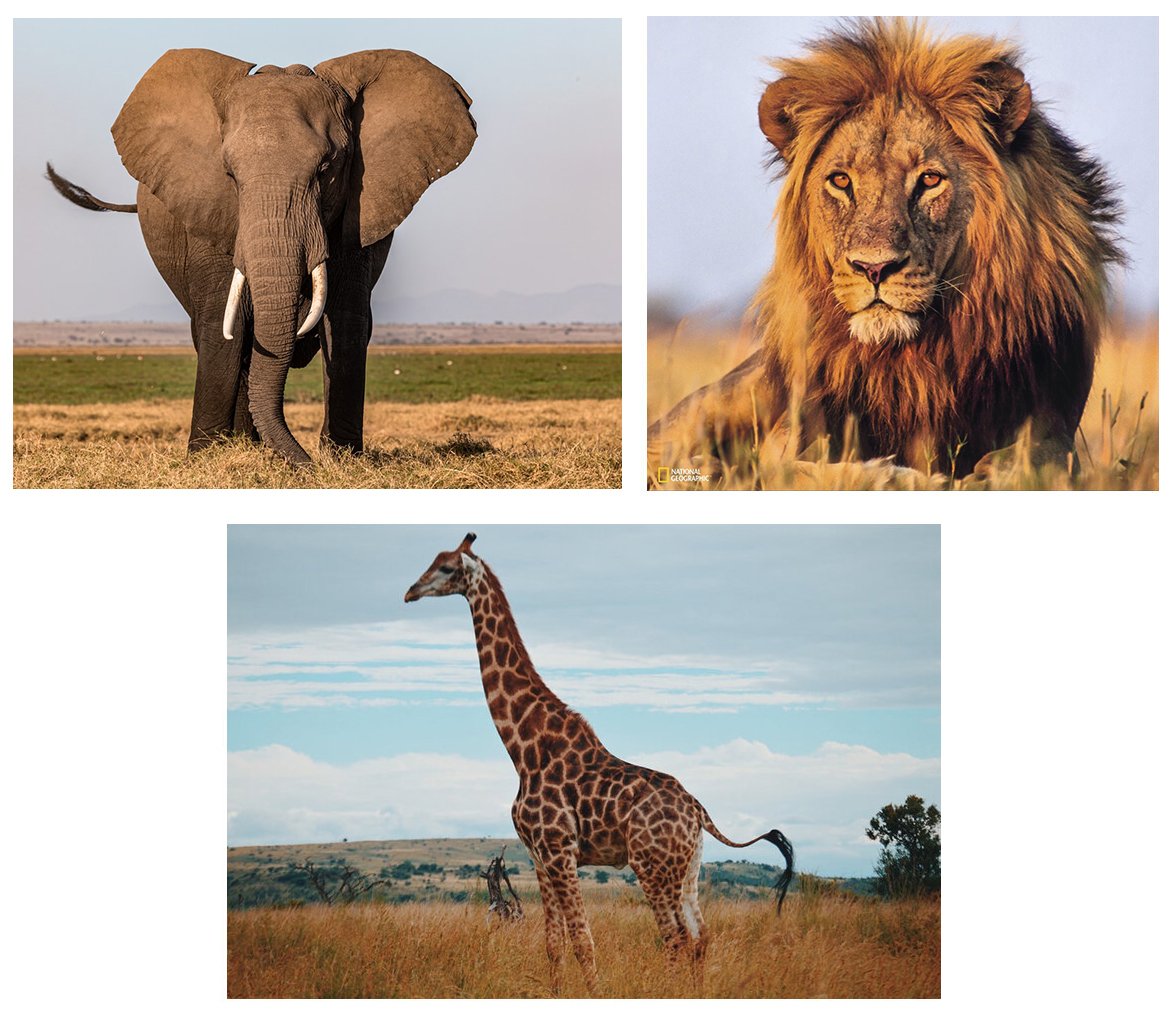

First, the vast majority of wildlife photographers use their cameras simply to SHOW us an animal, or to “point out” an animal:

Images like these are mostly just trying to “capture” what the human eye sees. They aren’t really trying to structure the image into any kind of expression, or narrative, about the subject.

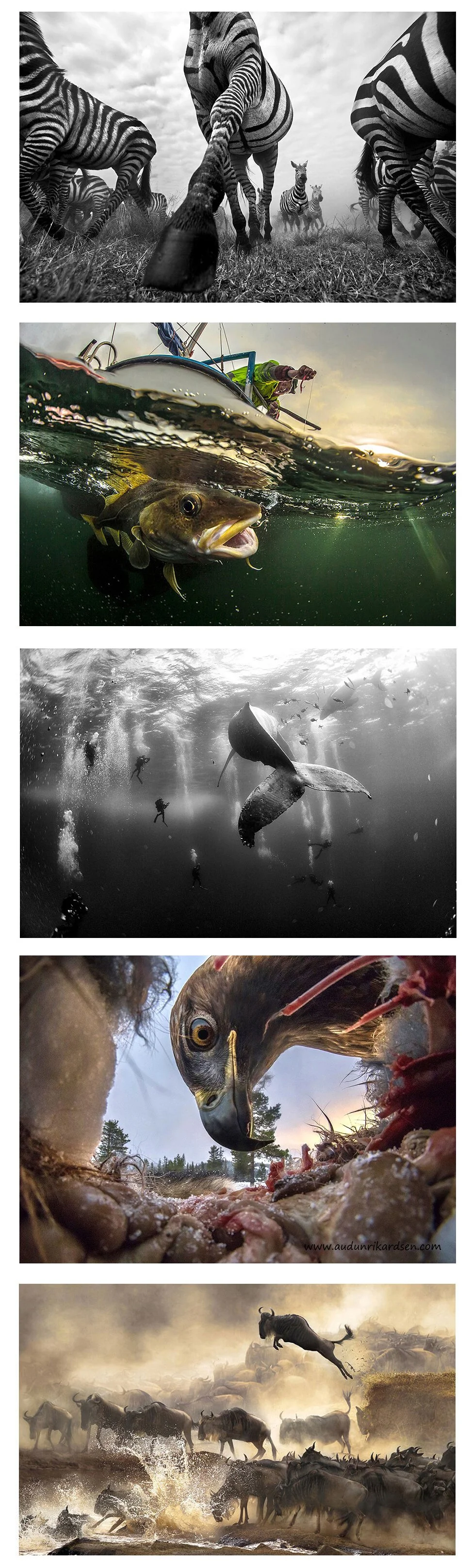

Whereas “Type A” wildlife photographers use their understanding of spatial relationships and movement differentials in order to narrate the wildlife, or to create relationships, or to portray the wildlife with some kind of momentous sensibility:

Next, most professional pet photography is shot like this — from a distance, in perfectly even lighting, and with nothing moving:

When, with just the tiniest bit of effort, we can use Light, Space, and Time differentials to shoot it like this:

You get the idea.

The basic gist of these comparisons is that, in each case, the first batch is entirely characterized by avoiding photographic variables, while the second batch is entirely characterized by utilizing and embracing those variables.

And this is the secret ingredient most people can’t put their finger on when it comes to what they perceive as “better” or “more dramatic” or “more creative” photographs.